Resurgence: the new commons

The end of 20th century has supposed a second resurgence of the commons, as they have gone from being almost unnoticed for scholars to be studied from various disciplines (namely Ecology, Law, Sociology or Politics, just to mention a few): many articles, books and special issues have been written covering different aspects of the commons, and even dedicated institutions1 and publications2 have been founded, to the point that authors like Laval and Dardot (2014⁄2015, p. 22) defend that they have become an academic discipline in their own right: the commons’ studies, which currently comprises almost all the social sciences’ studies (Laerhoven y Ostrom, 2007, p. 6). But commons are not only present in academia: they have become part of the vocabulary of non-academic discourses and anti-globalisation and social justice movements to the point that possibly the commons are currently more present outside academia than in it.

There are many reasons for such an explosion of commons: exogenous, like the ones outlined in the introduction (growingly aggressive neo-liberal policies, global crisis) and endogenous, like the reflexive work of key scholars such as Elinor Ostrom and Antonio Negri, the existence of study cases or the foundation of the International Association for the Study of the Common Property in 19893. But one of the main reasons is that it is such an appealing concept, and apparently easy to define, that it is indeed tempting to apply the idea of a collectively managed resource to most facets of life4, such as knowledge and culture (Hess y Ostrom, 2007), social relationships, music, health (Smith-Nonini, 2007), genetics (Cunningham, 2014) or even supranational and global resource domains (such as the atmosphere, outer space or cyberspace (Soroos, 2010; Stern, 2011)) and, as we will further elaborate, cities. These “new commons”, as they are often referred to, give a new dimension to concepts that despite are not new, they had never been studied from the collective action perspective5. Unfortunately, such an apparently simple and enormously suggestive idea is, in fact, an incredibly complex concept with multiple facets (political, social, urban, technological) and its meaning and scope is an issue of much controversy and debate. As Leif Jerram points out:

For Elinor Ostrom [...] ‘commons’ could be almost anything -including knowledge and computer code (Hess & Ostrom, 2007; Ostrom, 1990). For [...] Jeremy Németh the commons can be thought of as a whole range of things, from libraries, through the Internet, sidewalks, light from a streetlamp, to the atmosphere or some food [...]. And Hardt and Negri [...] define the commons (though they call it ‘the common’) in yet another way, unconnected to the others: the common is that valuable part of something, the value of which is not determined by its use value, or labor inputs, but created and given freely by potential users, like the trendiness of a bar (Jerram, 2015, p. 47).

This poses an indeed a problematic issue that derives from such a diverse concept. There are two opposed approximations to remedy this situation: the first one consists of providing a more generic interpretation of the commons that may fit on different contexts. Whereas the other one consists of creating a new taxonomy of the commons that may allow a classification of several subsets (or sub-species) of the commons that share specific sets of features. In the following chapters, we will examine how scholars have been tackling this disambiguation from the perspective of this two positions.

Redefining the commons

One of the first scholars who systematically studied the commons was Elinor Ostrom, who defined them as “a series of common-pool resources and public goods which are difficult, although not impossible, to exclude other people from” (Ostrom, Gardner, y Walker, 1994, pp. 6-7). As we will see in chapter 3.1, at that time, Ostrom was referring to a specific subset of natural resources (Common Pool Resources, to be more precise) that were collectively managed by a community. A similar definition, yet in a completely different context, would be given sixteen years later by Yochai Benkler, who underlined that one of the most salient points of the common, no matter its nature, is the fact that:

As opposed to property, is that no single person has exclusive control over the use and disposition of any particular resource in the commons. Instead, resources governed by commons may be used or disposed of by anyone among some (more or less well-defined) number of persons, under rules that may range from ‘anything goes’ to quite crisply articulated formal rules that are effectively enforced (Benkler, 2006, p. 61).

Both definitions share the fact that they provide a more comprehensive notion of property and they are focused on access to a common, which in both cases is a shared resource. However, Benkler did not have in mind natural resources, as Ostrom did, but something more intangible: software or knowledge, which obviously have entirely different characteristics.

Such differences in the resources’ nature have led other authors to focus not on the resource itself or the notions of property but on the communities that manage them and the social relations that are established between them. For example John L. Sullivan, states that

A commons arises whenever a given community decides that it wishes to manage a resource in a collective manner, with special regard for equitable access, use, and sustainability. The commons is a means by which individuals can band together with like-minded souls and express a sovereignty of their own (Sullivan, 2011, p. 234)6.

Amita Baviskar and Vinay Gidwani, portray commons as goods or resources which involve practices that rely on communities (thus denoting a logic of social relations) and, as such:

[Commons] involve ‘being-in-common’, or using resources in more or less shared, more or less non-subtractable ways through practices he [historian Peter Linebaugh] calls ‘commoning’. Such collective practices are distinct in at least two ways: (1) they underwrite production and reproduction through the commons they depend upon and oversee, and (2) they typically do so through variable local arrangements that are more or less equalitarian, incorporative, and fair. In short, commons need communities: without sufficiently robust communities of people willing to create, maintain, and protect them, commons are at risk of falling into disarray or becoming privatised (Baviskar y Gidwani, 2011).

By contrast, others like Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri (2009, p. viii) put both aspects of the commons –the resource and the community– on the same balance and define the commons both as a natural good (the natural environment, its resources and the products they yield) and a human product (the products of social interaction, such as codes, languages, affects, information and other forms of knowledge).

Other scholars define the commons in a negative way, this is, as an opposition to something, being enclosures7, market and capitalism the most quoted ones. These concepts are very interlinked and sometimes are used almost as synonyms by following a reasoning like this one: “enclosures destroyed the commons in order to favour capitalism which, pursuing the ideal of free market, only seeks economic profit”. Under this perspective, commons and capitalism are two opposing forces in constant conflict and what benefits one, harms the other8. Massimo de Angelis (2006, p. 147), exemplifies that reasoning by stating that “New enclosures, thus are directed towards the fragmentation and destruction of ‘commons’” and, as a result, commons could be considered as “social spheres of life the main characteristics of which are to provide various degrees of protection from the market”. However, Reinhold Martin (2013) warned that the commons are not just to be considered as a merely post-industrial upgrade of the modern state historically linked to the rise of capitalism, as they represent a different way. In order to support his claim, he quotes Hardt and Negri by saying that “what the private is to capitalism and what the public is to socialism, the common is to communism” (Hardt y Negri, 2009, p. 273). A similar reasoning is also shared by other authors like Observatori Metropolità de Barcelona (OMB) members who state that commons represent an alternative to the dichotomies market/estate and private/public. According to them, commons are social institutions based in local, communitarian and participative practises, aimed to provide answers to social demands and are managed in a non-market management of the resources (Observatori Metropolità de Barcelona, 2014). From this point of view, the words of Sullivan get a new perspective when he states that commons are a “vehicle by which new sorts of self-organised publics can gather together and exercise new types of citizenship”. Hence, they can even serve as a viable alternative to “markets that have grown stodgy, manipulative, and coercive” (Sullivan, 2011, p. 234), and that perspective is mostly used in current framing of urban commons.

From all these different conceptions and perspectives of the commons, we can state that all of them share the fact that commons are based on the action of sharing something between the members of a particular community. It is precisely that community the one that manages (governs) the commons and, in most cases, it does so in a non-market relation, this is: they do not look for economic profit. Laval and Dardot share this point of view and state that it is precisely the existence of a communitarian and democratic management of the commons what gives commons a meaning: “Lo que da sentido a la reunión de estos diferentes aspectos de los comunes en una designación única es la exigencia de una nueva forma de gestión ‘comunitaria’ y democrática de los recursos comunes, más responsable, más duradera y más justa” (Laval & Dardot, 2014⁄2015, p. 111). However, it is also true that apart from that, not only the term commons is used to designate very different things (Common Pool Resources, social relations, communities, software, cities...), but there is no consensus on its definition, or, quoting Maja Hojer Bruun: “with so many different uses of ‘commons’ it is probably impossible to formulate one generic definition of commons or to define one set of features that covers all the different kinds of existing and emergent commons” (Bruun, 2015, p. 154). As a result, this approach of trying to provide a generic definition has not solved the problem of commons’ disambiguation but has made things worse: the meaning of the commons has been broadened to such an extent that it could be argued that it has lost any meaning, as almost anything could fit on it and has often been used uncritically. As Sevilla-Buitrago states, the commons, then, seem to be more of a conglomerate of certain values or diffuse aspirations: “Los comunes —término que en la acepción inglesa que lo ha popularizado (the commons) se refiere tanto a la condición de lo común como a los espacios y recursos específicos para el soporte de la comunidad— se han convertido en el nodo alrededor del cual se condensan toda una serie de estrategias, deseos y aspiraciones más o menos difusas” (Sevilla-Buitrago, 2013). For this reason, Leif Jerram points out that it is easier to conclude that commons are associated with two moods: “good” and “old”. “The commons is good but it is also old” (Jerram, 2015, p. 48), although he alerts that this notion of historicity has to be questioned, “because it poses profound problems for the imaginary projects of commons activists” (Jerram, 2015, p. 48).

A new taxonomy for the commons

In opposition to try to provide a generic definition that may include all the possible types of commons, several authors have tried to create new taxonomies for the commons that would allow their classification according to specific features. In fact, scholars like Yochai Benkler or Charlotte Hess provided a generic definition but later on were forced to provide a classification that would narrow an otherwise too generic definition as well as would allow them to identify different sets of features shared between commons of the same type.

At the end of her career, Ostrom developed, alongside Charlotte Hess and their colleagues at the Workshop in Politechnical Theory and Policy Analysis at Indiana University the Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework aimed to analyse knowledge as a common (Hess & Ostrom, 2007). That framework ultimately led them to study new types of commons of different types and nature that they grouped according to two parameters: degree of exclusion and subtractability, which resulted in the 2x2 matrix that can be seen in table 2.1.

| Subtractability | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||

| Exclusion | Difficult |

|

|

| Easy |

|

|

Tabl. 2.1: Types of goods classification. Source: Hess & Ostrom (2007)

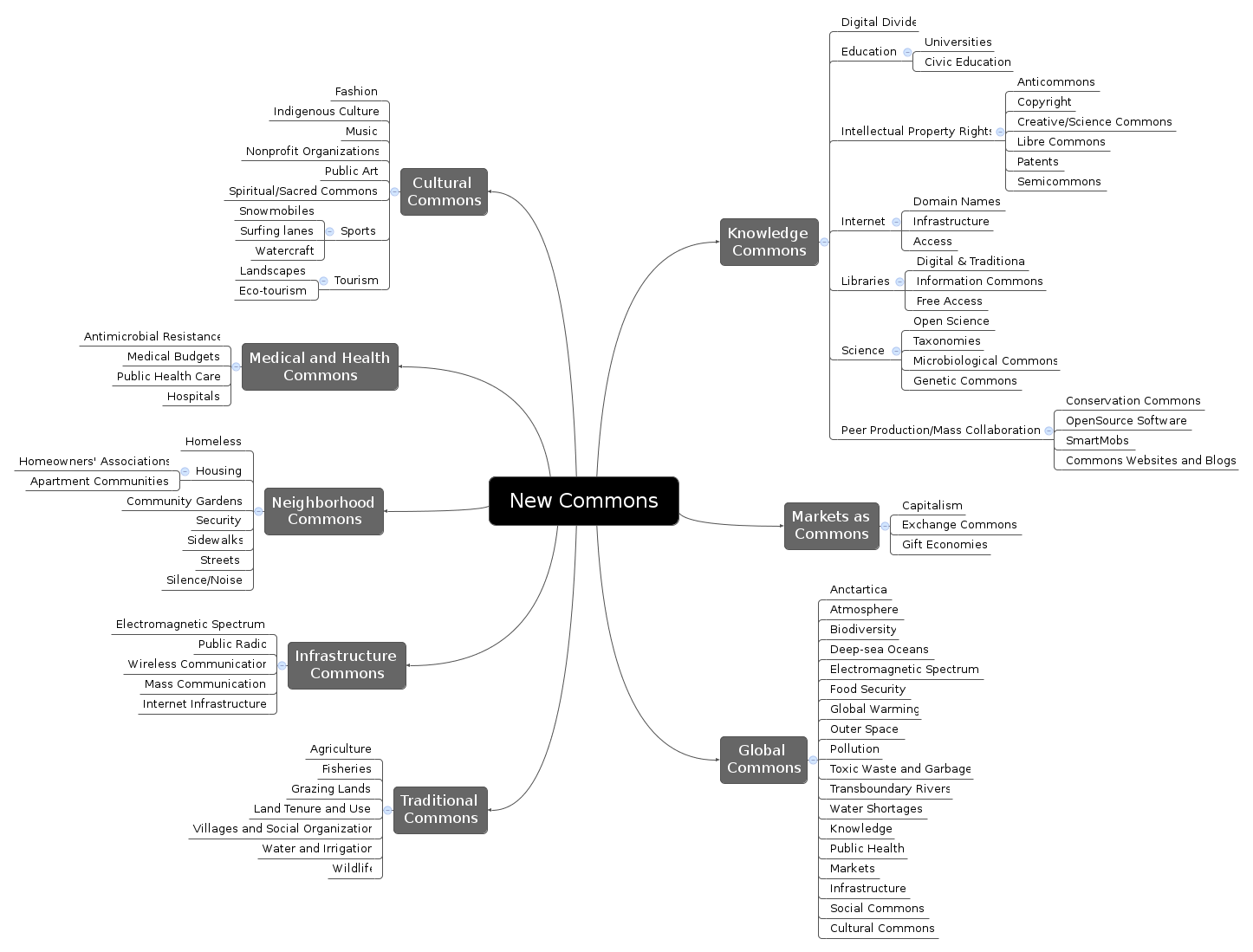

Although Ostrom would not go any further on this topic, Charlotte Hess continued her research on what she called “non-traditional Common Pool Resources”. She observed that, due to the emergence of new technologies that allowed the capture of previously uncapturable public goods (such as the Internet, genetic data, outer space…) on the one hand and to the reconceptualization9 as commons of already existing publicly shared resources (like streets, playgrounds, urban gardens, hospitals…) on the other, a myriad of “new commons”10 emerged at the end of 20th century. These new types of commons did not have any connection to traditional commons studied by Ostrom and, consequently, introduced an enormous diversity difficult to tackle without taking into account their own set of differences. As a result, she proposed a mapping of these new commons into the following main sectors according to their type of resources: cultural commons; neighbourhood commons; knowledge commons; social commons; infrastructure commons; market commons; and global commons. In turn, she provided several examples of commons within these sectors and their subsectors, resulting in the exhaustive mind map displayed in the figure 2.2. However, her mapping was problematic too: as she admitted (Hess, 2008, p. 5), such classification in groups was somewhat arbitrary, as there were evident overlaps between sectors in some cases and there were some groups which had a clear physical dimension whereas others were in fact examples of social groups or collective action.

Fig. 2.2. Charlotte Hess' mapping of the "New Commons".

On the other hand, Yochai Benkler made an entirely different classification, as his proposal resulted from the combination of two parameters: “The first parameter is whether they are open to anyone or only to a defined group. […] The second parameter is whether a commons is regulated or unregulated” (Benkler, 2006, p. 61). This combination of variables results in four types of commons that are summarised in Table 2.2 below.

| Paramter | Variation | Examples | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Openness | Open to anyone | Oceans, air, highway system | |

| Open to a defined group only | Pasture arrangements and most of Ostrom’s CPRs described on Governing the Commons are of limited-access | “These are better thought of as limited common property regimes, rather than commons, because they behave as property vis-à-vis the entire world except members of the group who together hold them in common” | |

| Regulation | Regulated | Sidewalks, streets, roads and highways | The constraints, if any, are symmetric among all users and cannot be regulated by a single individual |

| Unregulated | Air |

Tabl. 2.2: Benkler’s taxonomy for the commons.

Other examples of classifications are the ones provided by Bru Lain Escandell (2015a), who distinguishes between natural and digital commons (each of them with their own set of features, challenges and problems); by Hardt and Negri, whose two types are divided into the common wealth of the material world (water, air, soil...) and the results of social production that are necessary for social interaction and further production (knowledge, languages...)11; or by International Globalization Forum0, which Ana Lucía Gutiérrez Espeleta and Flavio Mora Moraga (2011, p. 129) summarise as the following three type of common goods. The first of them are natural biological resources upon which human life depends on (examples of this group include water, air, soil, woods, fisheries… –this group, hence, would be the same as the CPRs portrayed by Elinor Ostrom). The second group of collective cultural creations which includes knowledge and culture. And the third one encomprises social commons aimed to guarantee public access to health, education and social security. This somewhat generic classification pushes Gutiérrez Espeleta and Mora Moraga to make their own proposal conceptualising commons as follows:

Commons as a resource: the emphasis here is put on an object which does not belong to a single person or entity but is shared by a group or community. This kind of commons are “things” that belong to anyone by the sole fact of belonging to the human race and thus respond to the “common interest”.

Commons as social relations: what defines a common is not the resource per se but the groups of people that are formed around it in order to collectively manage it and the type relationships that are woven between their members.

Commons as resources leading to political action: the emphasis is put on the political motivation and organisation oriented to achieve certain results aligned to their claims.

In fact, Gutiérrez Espeleta and Mora Moraga are well aware that the limits between these groups are blurry and, hence, state that these are not exclusive options but complementary, which doesn’t help much in the classification of the commons.

With such a variety of diverse classifications, we attempted to create our own one summarising some of the previous ones and resulting in the following table:

| Resource | Examples | Scholars | Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural resources | Forests, meadows, moors, water, fisheries... | Ostrom, Bollier | Exclusive, limited |

| Culture and knowledge | Creative commons’ licences, books and writings, music, pictures... | Lessig, Hess, Ostrom | Non-exclusive |

| Technology | FLOSS, Open Hardware | Stallman, Benkler | Non-exclusive |

| Cities and urbanism | Communitarian equipments | Harvey | Non-exclusive |

| Genetic materials | Scharper and Cunningham | ||

| Food | Soilent | - | Exclusive |

| Energy | Somenergia | Exclusive/Non-exclusive |

Tabl. 2.3: Commons’ taxonomy proposal according to the type of resource.

Unfortunately, any of these attempts to classify the commons can easily be refuted because it is not possible to cover the whole spectrum of the commons. However, these attempts evidence an emergent tendency consisting of adding an adjective to the term “common” in order to narrow its meaning. An example of this tendency is the term “urban commons”, which are the study object of this research and will be further developed in upcoming chapters.

The reasons for such failure are either because the selection criteria are not clear or because despite being clear, they do not suffice to classify the great variety of things, relationships and challenges that exist worldwide and beyond which are often referred to as “commons”. But their main problem is that all these classifications share the fact that they conceptualize the commons basically as shared resources, whereas as Gutiérrez Espeleta and Mora Moraga timidly introduced (and as we will further elaborate on chapter 8) there are other dimensions of the commons that go far beyond the resource itself. This perspective enormously contributes to a broader understanding of the concept yet, at the same time, introduces a far more considerably complexity that cannot be tackled by any of the classifications provided above nor by providing general definitions.

Such as the “International Association for the Study of the Commons” ([http://www.iasc-commons.org/]), a non-profit founded in 1989 to promote the understanding of institutions for the management of resources that are or could be held or used collectively as a commons by communities in developing and industrialized countries.

[return]Like the “International Journal of the Commons” ([https://www.thecommonsjournal.org/]), an interdisciplinary peer-reviewed open-access journal, dedicated to furthering the understanding of institutions for use and management of resources that are (or could be) enjoyed collectively, being them part of natural world or created by humankind.

[return]As oultined by Van Laerhoven and Ostrom (2007), the International Association for the Study of the Common Property, that would become the International Association for the Study of the Commons in 2006 to broaden its focus, was a consequence of these previous and important events that put together scholars of different disciplines: the series of symposia and workshops, organized by Bonnie McCay and James Acheson in 1983 and 1984, the establishment of the National Research Council (NRC) Committee on Common Property and the organization of a conference in Annapolis, Maryland in 1985 (Laerhoven & Ostrom, 2007, pp. 4-5).

[return]- Visit Nonini (2007)’ for more information. [return]

As Maja Hojer Bruun states, “\‘New commons\’ are not necessary new per se, but framing collective resources such as knowledge or music as commons is a way of pointing out that these resources used to be or should be owned and managed collectively as a common good.” (Bruun, 2015, p. 154).

[return]In this same essay about Open Source Software, Sullivan states that commons are a “vehicle by which new sorts of self-organized publics can gather together and exercise new types of citizenship” and thus they can even serve as a viable alternative to markets “that have grown stodgy, manipulative, and coercive”, another topic that we will develop.

[return]The concept of “enclosures” is also being redefined, as it has also been used in recent literature in many different contexts and situations other than the parliamentary enclosures with more or less fortune. Most of the times the physical dimension of the enclosures (putting fences to a resource to prevent the access to it) has been omitted and the term “enclosure” is used as a synonym of “privatization”, which according to Hodkinson is just a part of the enclosure itself, along with dispossession and capitalist subjectification, and it is only when the three aspects have taken place that we can talk about enclosures (Hodkinson, 2012, p. 515).

[return]Baviskar and Gidwani seem to go further stating that both can’t coexist, as “The destruction of common resources and the communities that depend upon them is a long-standing outcome (some would argue, prerequisite) of capitalist expansion” (Baviskar y Gidwani, 2011, p. 43), and Hodkinson argues that the creation of (Urban) commons prevents the expansion of capitalism (Hodkinson, 2012, p. 516).

[return]According to her, the conference organized by the International Association for the Study of Common Property (IASCP) in 1995 with the theme “Reinventing the Commons” highly contributed to favour those reconceptualizations (Hess, 2008, pp. 2-4).

[return]Hess decided to rename “non-traditional Common Pool Resources” into “new commons” for two main reasons: “First, it indicates that there is something different about this kind of commons. Second, it challenges us to think about the general term ‘commons’ –a term frequently applied yet rarely defined” (Hess, 2008, p. 3).

[return]Hardt and Negri understand the common (in singular) as a combination of two types, being the first one “the common wealth of the material world—the air, the water, the fruits of the soil, and all nature\’s bounty — which in classic European political texts is often claimed to be the inheritance of humanity as a whole, to be shared together.” (Hardt & Negri, 2009, p. viii). The second type of commons, which they consider to be even more significant, includes “those results of social production that are necessary for social interaction and further production, such as knowledges, languages, codes, information, affects, and so forth” (Ibid.). As they both state, contrary to the environmental approach that we have developed on chapter 2.1, this notion of the common “does not position humanity separate from nature, as either its exploiter or its custodian, but focuses rather on the practices of interaction, care, and cohabitation in a common world, promoting the beneficial and limiting the detrimental forms of the common” (Hardt & Negri, 2009, p. viii).

[return]