An archaeology of the commons

As stated previously, the concept of the commons is not new at all. For instance, Christian Laval and Pierre Dardot (2014⁄2015, p. 30) argue that the origins of the common date from the notions of the ancient Greek institution of the common (koinôn) and “to put in common” (koinônein) portrayed by Aristotle who, in turn, stated that citizens were the ones who deliberate in common in order to decide what is best for the city and what is fair to do (Aristotle, 4th Century BC./2004)1. Lewis Mumford (1989, p. 58) mentions the existence of commonly managed water resources in old Mesopotamia and Peter Linebaugh (2008, p. 40), as well as Laval and Dardot (2014⁄2015), state that commonly managed resources are rooted in Christian tradition and the Old Testament2. Other authors, like Derek Wall (2014, pp. 23-31) trace the existence of commons outside Europe or occidental culture, pointing out that there are other historical examples in India or Mongolia.

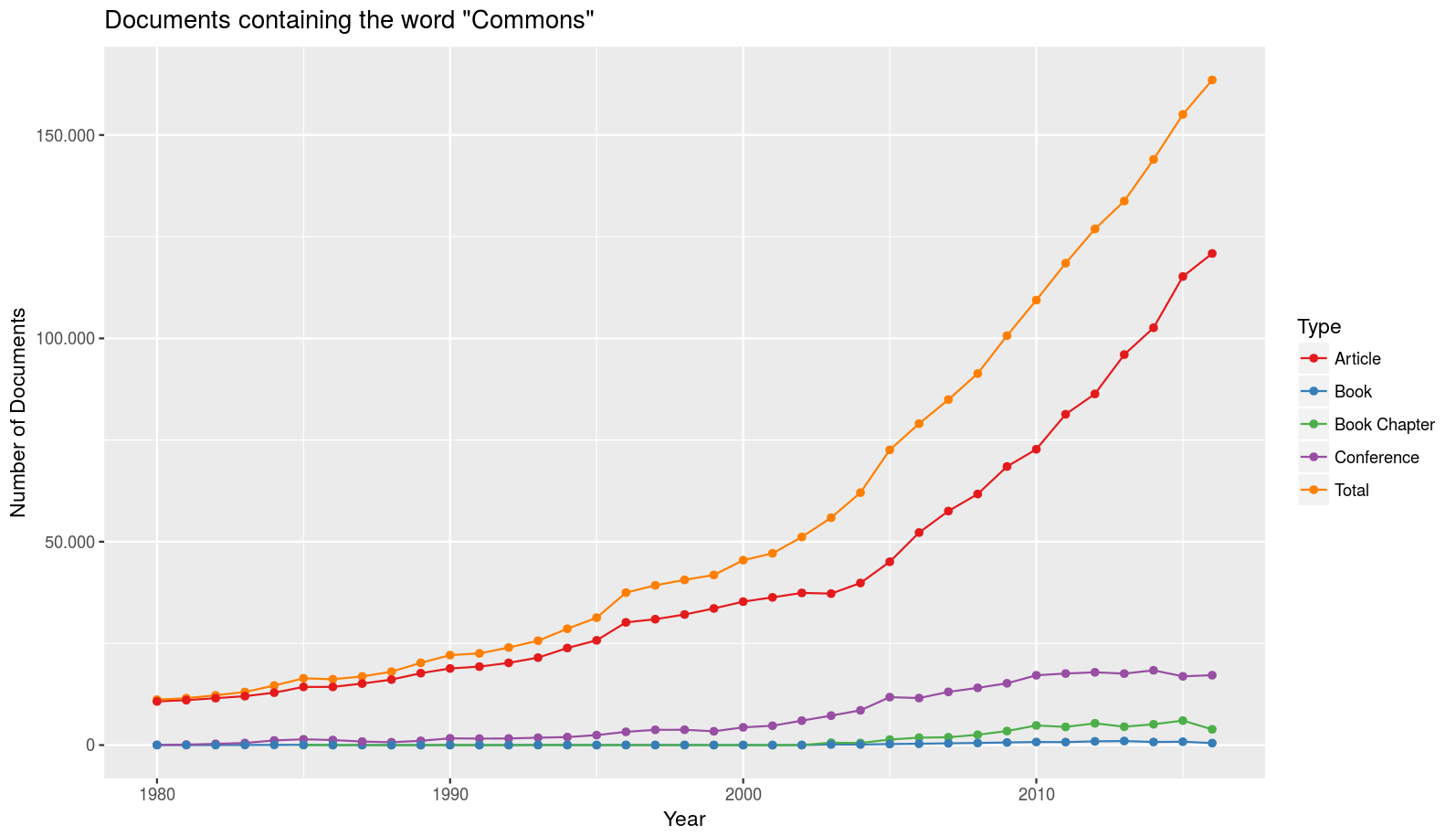

However, despite its origins are unclear or blurred, there is a growing number of scholars contributing to the research field of commons’ studies (figure 2.1), and today’s conceptualisation on the commons seem to agree with historian Peter Linebaugh (2008), who traced its origins to the Magna Carta written by King John of England on 15 June 1215. Most of them, hence, share the same imaginary when they refer to the English commons to demonstrate that are something old and good and to outline the parliamentary enclosure acts that put an end to most of them in order to justify their positions. This shared imaginary, however, has been studied from different perspectives, as we will further develop in the upcoming pages in which we will try to define the concept of the commons.

Fig. 2.1. Evolution of documents containing the word “Commons” in Scopus database (1980-2016)..

From the Spanish perspective, Nebrija’s Dictionary, a Spanish dictionary written in 1492, has an entry which explicitly defines the common3 as those activities which benefit everyone (Nebrija, Colon, y Soberanas, 1492⁄1979, our translation.).

1. Year 0: the old English Commons and Parliamentary Enclosures

There is a big core of literature pointing out that common lands (colloquially known as “Commons”) were frequent in medieval Europe. Spain was not an exception on this4, although they were more frequent and documented in pre-industrial England as the large literature shows (Beresford, 1998; de Angelis, 2002; Fairlie, 2009; Mingay, 1998; Neeson, 1996; Sevilla-Buitrago, 2013; Wordie, 1983). For instance, by the year 1600, open fields represented 3⁄5 parts of all arable lands and 53% of all the surface of England (Sevilla-Buitrago, 2013; Wordie, 1983, p. 491)5. It was frequent that the owner of the lands would let part of it to members of the parish councils for their communal use, especially after the harvest and fallow. However, it would be highly imprecise to refer to the commons as a homogeneous ethos: Medieval commons was a phenomenon which covered a vast geography where communication was not always easy, and a long period of approximately four centuries that cover the slow decline of feudalism (from the end of 14th century to second half of 15th) and the birth of industrialization in 18th century.

By taking these figures into account, we can easily deduce that there is not one but several ways of understanding and practising the commons, as the concept of common lands has been evolving to adapt to specific casuistry: after all, the societies that produced them differed substantially in time and geography. As an example, some common lands were part of a state which belonged to a tenant and, thus, they were tied to a manorial system6 regulated through Manorial Courts and appurtenant rights. On the other hand, some others were governed by local institutions (Parish councils) through a complex system of customs, oral laws and moral rules in order to watch over all community members’ needs. But not only there were differences in the commons’ governances and in who their ultimate owner was, but also in the type of commons, being the most usual the following ones: arable fields, usually divided into smaller lots for rotation crops; open pastures for pasturing cattle, horses, or other domestic animals; piscaries for fishing; turbaries for taking sods of turf for fuel; or estovers for taking wood (usually limited to smaller trees, bushes and fallen branches).

Be it as it may, no matter if commons were created because of laws (Manorialism) or customs, and despite their great variety and complexity in their governance, they always involved two features. First, open access to a land that belonged to a landlord who ceded part of it to anyone to benefit from under certain conditions (may it be during a specific period –fallow, pastures after harvest...– or to a specific area –usually fallow lands or wastelands). And second, a self-organised community that collectively managed the resources that may grow or could be found on those lands so the higher number of people could benefit from them without detriment to other members, usually landless who almost had no possessions. Again, the particularities of each community differed enormously from one to another, as each one was independent and was organised by councils were all decisions were made through assemblies.

Although there is no clear consensus on the reasons for why such a particular system (often quoted to as “inefficient”) endured so many centuries, it is likely that, as pointed out by Jonas Holst (2016), it was because commons provided a response to particular problems that involved a sort of conjoint action to overcome them (Dahlman, 2008, p. 28). From this perspective, this particular structure benefited landlords, as it served to keep the forests clean (preventing natural disasters like fires or floods) and ready for production. Commoners were also benefited, though, as the same structure provided a degree of freedom for most of the less privileged classes in rural areas7, who where able to access to natural resources for their own use that allowed them to survive without having their own land or a proper job (Dahlman, 2008, p. 141; Neeson, 1996, p. 663; Sevilla-Buitrago, 2013; Thompson, 2009, pp. 100-101). This resulted in a life-form out of capitalist mode of production, based on customs and social practises that allowed commoners to “live off the land rather than on it” (Neeson, 1996, p. 66) to the extent that, as E.P. Thompson states, “access to an extensive common could be critical to the livelihood of many villages” (Thompson, 2009, p. 177).

However, between the end of 17th century and the beginning of 18th, started to take place the slow decline that would eventually end with the common lands and with the societies organised around them: the parliamentary enclosures. These so-called parliamentary enclosures were a set of more than 4,000 changes in the British legislation promoted by the parliament with a common denominator: the access’ limitation to the common lands by means of fences, dykes, hedges or trenches preventing access to them to anyone but their legal owner (Fairlie, 2009). In other words, enclosures were a combination of privatisation plus limiting access to those resources that had been open for centuries and provided means of subsistence to the most deprived ones.

Although there are documented cases of enclosures during Tudor dynasty, which were basically unilateral fencings made by landlords in order to convert common lands into pastures (Beresford, 1998, p. 28), these practises started to spread little by little to the point they became institutionalised, coordinated and legislated like the aforementioned parliamentary enclosures under Stuart and Hannover dynasties.Several reasons led to this situation, being the most evident and documented ones those that make a spatial lecture and see the land as a mean to improve the economy8. From that perspective, the transformation of the open common lands into private pastures made them more efficient and more profitable in economic terms and, as a result, England could compete in the recently opened international market for grain distribution, which was dominated by Poland, Prussia and The Netherlands (Sevilla-Buitrago, 2013, sec. Implicaciones para la historiografía de la planificación: desposesión y cambios de escala en la concepción de los procesos territoriales) at that time.

But enclosures were far more than just a physical transformation of the land structure and the landscape. From a social perspective, they also provoked a profound transformation with dramatic consequences for the millions of people (Fairlie, 2009, sec. Parliamentary enclosures) who depended in more or less degree on the common lands but didn’t own any: the accumulation of wealth in the hands of a small elite on the one hand and the dispossession9 of a vast social group on the other. By preventing the commoners to access to the lands that brought their means of subsistence, their lifestyle was also destroyed and all that people were expelled from the villages where they had their previous way of life. This situation forced commoners and former small land-owners to initiate a rural exodus to the cities with the expectations of finding a job opportunity in the only possible place they could be accepted with no prior experience and where no questions were asked: a growing industry which demanded loads of cheap labourers in order to expand and extend their hegemony to new international markets.

Some scholars defend that, in fact, parliamentary enclosures responded to a conscious decision to get rid of a social group that could survive without even working and, hence, was considered as lazy, filthy and annoying10. An example of that perception on the commoners can be found in the pamphlet written by Thomas Wilkinson in 1812, which he used to try to convince his neighbours against the enclosure of Yanwath Moor, in order to prevent what, according to him, would lead to a more than probable negative consequences for the present and future of the inhabitants of his native village, and the neighbouring ones (Wilkinson, 1812⁄2013, p. 2). As Sevilla-Buitrago (2013) points out, the following fragment is worth reading, as it is an excellent document that can help us to get an understanding of the perceptions that wealthy people had regarding commoners and commons:

[…] The fifth and last argument is the one that has been most frequently used, and is, that by inclosing (.sic) the Common we should get quit of the Potters! [...]. However, as we have got hold of the poor Potters, let us keep them a little and treat them kindly, for I believe they are hitherto strangers in print. [...] It is said they are a nuisance; a rat is a nuisance in a house, but what wise man would pull down his house to get quit of a rat? But they at times exhibit scenes of riot and disorder; this I lament, and would join in endeavouring to suppress such disorder. Public Houses too, exhibit scenes of riot and disorder: ale contributes to this, and has done more harm than all the Potters lodging on all the Commons in England. Yet; who would promote an act of parliament to prohibit ale? Surely nobody.

Ale has done a deal of good, and Potters some. I have seen, five or ten miles from market, the Potters spread their wares on green hills, while the village maids and matrons gathered around, to become purchasers. I have not investigated the question whether these sort of purchases are made more reasonable at Penrith or by the Black Fells. The villages at the foot of that long chain of mountains, and other villages, are accommodated by these perambulating dealers, and perhaps on as reasonable terms. Then the village matron, far from market, escapes the perplexity and loss that often occur from the stumbling of her horse and the downfall of her basket, or the breakage of her crockery from the breaking of her apron-string. We see differently, and perhaps I have beheld the Potters with other eyes than some of my neighbours (Wilkinson, 1812⁄2013, pp. 30-31).

But from a Marxist perspective, as Sevilla-Buitrago (2012, 2013) explains, in fact, the goal was not to destroy the commoners for the sake of its morals but to transform them into a new social class so dependent on their new jobs far away from their original hometowns in order to survive, that could be easily malleable to their patrons’ needs.

Without open lands and without commoners that could manage them, almost all the commons disappeared, not only from England but also from Europe, where similar processes also took place11. However, this process of several centuries that brought to the almost extinction of the commons led to a new history of rebirth. Not only some similar commons survived throughout Europe to present days12, but at the end of the 20th century they would experience a second renaissance with a renovated and broader meaning13 that take this snapshot picturing the decline of the commons as the starting point in their propositions. It is such a critical concept in today’s literature that it has been studied and quoted by most scholars, to the point that there are very few papers that do not mention the old English commons or the concept of the enclosures.

The notion of the commons has, however, evolved since then: Aristotle’s was concerned only on the action of putting something in common (which was the only prerequisite) and thus, he was for private property if it was to be used in common, after all, as Even Elinor Ostrom would quote centuries later, he was aware that “what is common to the greatest number has the least care bestowed upon it. Everyone thinks chiefly of his own, hardly at all of the common interest” (Ostrom, 1990, sec. 1.1) and private property held in common could be a solution to one of the main concerns of the commons: that of the free-rider.

[return]“When you reap the harvest in your field and forget a swathe, do not go back to pick it up; it shall be left for the alien, the orphan, and the widow” (Deuteronomy, 24:19).

[return]The exact Spanish word used on the dictionary is “Procomún” which is often translated into English as “Commons”.

[return]Visit ‘Los comunes de villa y tierra en Guadalajara’ (Herrera Casado, 1989) and Los comuneros (Pérez, 2006) for a more comprehensive description on how Commons were institutionalised by the King and their importance. Just to give an idea of their extension, Herrera quotes: “La estructura socio-económica y político-administrativa de los Comunes de Villa y Tierra, se expande desde el siglo XI a través de un ancho territorio que media entre la orilla izquierda del río Duero y la derecha del Tajo. En ese amplio margen cabe entera la Extremadura castellana, la Transierra o grupo de tierras al sur de la Cordillera Central, y el denominado Reino de Toledo. Abarca también algunos fragmentos del norte del Duero por Soria y del sur del Tajo por las serranías conquenses. Y se expande en su estructura peculiar por tierras de la Extremadura leonesa, hoy provincia de Cáceres, y aun por las del Bajo Aragón en Zaragoza y Teruel o las sierras de Cazorla en torno a Ubeda y Baeza. Solamente en la Extremadura castellana, en la que gran parte de las tierras de la actual provincia de Guadalajara quedaban incluídas, existieron en la Baja Edad Media un total de 42 Comunes de Villa y Tierra”.

[return]

Common lands are still recognized on current Spanish Constitution, even though their existence has been dramatically reduced due to several enclosure acts, such as Madoz’s law in 1855, which expropriated most of common lands in Spain.Leif Jerram, however, questions this positive widespread point of view and provides different figures in order to argue that commons are not to be considered representative at all but just an idealized imaginary, as according to him “Common land came with labor duty to the landowner which was gradually commuted to a money payment. The class below the commoners (that is, most people) did not have right to productive common field, only limited scavenging rights on marginal land. The landless poor had, under the commons system, access to only 4% of cultivated land. The amount of land (called ‘waste’) available to the genuinely poor in 1750 […] was c. 1m acres, and was used by >2m people” and that around 1700 “only 21% of the farm land in England was ‘common’” and thus, common land farming was something exceptional which generally belonged to most prosperous families, “a form of bondage and privilege” “Significantly, around 1700 […] only about 21 per cent in England was common land”. (Jerram, 2015, pp. 57-58)

[return]Manorial systems, an antique system originally founded on feudalism, granted rights of land use to different classes through regulation of specific courts and appurtenant rights. Sevilla-Buitrago (2013) explains that, according to property regimes, Manors could be divided into three parts: A) demesne lands, controlled and used by the landlord; B) tenemental lands yielded by the landlord to third parties; C) waste lands like forests, footpaths, ponds and the like.

[return]This included the poor, the landless and widows amongst others, widows being a particularly vulnerably collective, to the point that were explicitly included in the Carta Magna Manifesto as to be protected: “ At her husband’s death, a widow […] shall have meanwhile her reasonable estover in the common. There shall be assigned to her for her dower a third of all her husband’s land which was his in his lifetime, unless a smaller share was given her at the church door.” (Linebaugh, 2008, p. 284).

[return]It is the first time in history that urban speculation takes place, and it could be considered as planning for the wealthy: “La acumulación y consolidación de propiedades era el modo natural de obtener ganancias para los terratenientes rentistas; en un contexto de ciclos acelerados de especulación inmobiliaria tras la revolución del XVII, el enclosure se convirtió en la clave para penetrar las tierras comunales, jugosos nichos de mercado de otra forma inalcanzables. Por otra parte, los objetivos del cercamiento no siempre tenían un carácter exclusiva y puramente económico.” (Sevilla-Buitrago, 2013).

[return]The concept of “dispossession” will become crucial in the framing of the commons, which will be further developed in chapter 3.3.

[return]At this respect, Leif Jerram states that “The reasons for ending commoning between 1550 and 1850 were powerful and rational, not arbitrary or conspiratorial» and argues that «Many commoners voluntarily enclosed their lands, either because it delivered an increase in productivity, or because they could not get on with other commoners” (Jerram, 2015, p. 58).

[return]In Spain, for example, there have been subsequent privatizations, like the confiscation of the communal lands in 1855 by the minister of finance Pascual Madoz Ibáñez. Ben White et al. introduce a collection of literature regarding a new set of land enclosures that have happened throughout history in different places of the globe, specially in developing countries (White, Borras Jr, Hall, Scoones, y Wolford, 2012).

[return]Visit Bravo and Moor (2008) for a comprehensive list. There are also some cases of commons as collectively managed natural resources in Spain, like the communal management of the water in the Huertas of Valencia, Murcia, Orihuela and Alicante (Ostrom, 1990, pp. 69-81), or the “Montes vecinales de mano común” in Galicia (García Quiroga, 2013).

[return]Elisabeth Blackmar, though, argues that the concept of the commons has been perverted since then, and that its essence consists of the right that each individual possesses in order not to be excluded from the uses or benefits of resources (Blackmar, 2006, p. 51).

[return]