The institutional approach: commons as collectively managed resources

As we have previously seen in section 2.1, there have been numerous examples of documented commons through history and until the end of 20th century the term was exclusively used to refer to natural resources that were managed collectively. Surprisingly enough, though, there has not been a significant literature corpus theorising on them until present days. In fact, the commons had been almost unnoticed by academia until Elinor Ostrom defied the established belief that commons were an obsolete and inefficient way of survival, vestiges of an old rural era superseded by an industrial and efficient one. Such a belief was in turn based on the Hegelian idolization of private property and on an interpretation of The Tragedy of the Commons, a paper written by Garret Hardin (1968). Although their positions can’t be more opposed, both share the fact that managing natural resources outside private property poses not few challenges that are to be overcome if they are to be successful (Ostrom) or, on the contrary, become a tragedy (Hardin) if they are not tackled correctly. In the following pages we will compare both visions and how they have profoundly influenced today’s conceptions of the commons and how they have opened the door to new interpretations that go far beyond natural resources, to the point that they have set the basements of so-called multidisciplinary and growing Commons’ studies (Laval & Dardot, 2014⁄2015, p. 22).

The Tragedy of the Commons

In his seminal article The Tragedy of the Commons, the ecologist Garrett Hardin (1968) was concerned about the problem of population growth and its negative consequences in a finite world like ours. As Hardin points out, Jeremy Bentham’s goal of “the greatest good for the greatest number”, which according to the philosopher is the moral principle in which utilitarianism is based since is the final measure of what is “good” or what is “wrong” (Bentham, 1776, sec. Preface), can only be achieved with an optimal world population which is less than the maximum. The reason is that humans need food as a source of energy to survive, work and for all forms of enjoyment, and food is a finite good. So, according to Hardin, energy is both the problem and solution: on the one hand is the final measure of what this “good” that is to be shared is and on the other hand its acquisition that is the problem.

Hardin exemplifies this problem with William Forster Lloyd (Lloyd, 1833⁄1980) pamphlet which described a pasture open to all (this is, a common land like those described in the previous chapter) which is used by several herdsmen who seek their own benefit. Hardin points out that in a given moment each herdsman may face a dilemma when asking themselves about the consequences of adding one more animals to their herd. By doing so they may get a positive effect for themselves, since they will increase their benefits by one; but also an adverse effect, since at a certain point they will have to face the overgrazing consequences, such as animals being run short of pasture or soil’s exhausting. But the most significant consequence is that whereas these side-effects are to be faced by all the herdsmen who share the same pasture, only the person who has the bigger herd will benefit from this fact, making a positive balance for him. This is precisely the tragedy of the commons he denounces, since this means that individual goals are not shared by all the commoners1.

The relevance of Hardin’s publication goes far beyond the field of biology2 and is twofold: on the one hand, it has been considered to originate a new research field, that of the commons (Berge & Laerhoven, 2011, p. 161), as prior to his publication, articles containing words such as “commons”, “common pool resources” or “common property” on their titles were scarce (Laerhoven & Ostrom, 2007, p. 5). On the other hand, his position was taken as an irrefutable argument for the superior efficiency of private property rights concerning shared land and resources, and therefore as a justification for privatisation3. It is important to point out, however, that Hardin never made such assertions: after all, his concerns were not about the commons but planet’s overpopulation. He simply used the example of a common pasture as a metaphor to expose the problems of an uncontrolled cattle when its size grows beyond certain limits and as a justification for claiming strong intervention by the State on this matter.

These interpretations of Hardin’s work evidence that the study of the commons has been based on strong presumptions which are only valid under certain circumstances4 and in turn can only pose two (and therefore, biased) possible positions about property: either public or private. Following this reasoning, the only solution to such tragedy would be either a regulated system based on private property and the market, in which every individual would only be responsible for their property, or a firm control from the State, through planning, laws and hierarchy.

Questioning these two facts was, precisely, the ultimate goal of Elinor Ostrom when she decided to write “Governing the Commons”, a seminal article from 1990 which was to dramatically change the commons’ conceptions and literature.

Commons: an alternative to market and state

Ostrom makes crystal clear at the beginning of her book5 that “Governing the Commons” is to be considered a critical work which is to question dominant positions regarding to Common Pool Resources (CPRs), which she defined them as a “natural or man-made resource system that is sufficiently large as to make it costly (but not impossible) to exclude potential beneficiaries from obtaining benefits from its use” (Ostrom, 1990, p. 7). In fact, in the first part of her book (chapters 1 and 2), Ostrom tries to figure out whether private resources’ management is better than common property resources (as Hardin stated and has been taken for granted in many other situations since then6) and she does so by reflecting on three broadly influential models: the tragedy of the commons; the prisoner\’s dilemma; and the logic of collective action. By doing so, Ostrom concludes that, against popular belief, there is not a single way to solve the problem of the commons (Ostrom, 1990, pp. 13-14). Instead, she points out that there is another possible way to solve CPRs problems of governing collective action (Ostrom, 1990, pp. 15-20) which is neither a coercive force from the state7 nor the privatisation of property rights, which were apparently the two “only” possible (and opposed8) ones at the time of writing: that of self-governed CPRs based on historically grown, institutionalized rules and practises in which “a group of principals can organize themselves voluntarily to retain the residual of their own efforts” (Ostrom, 1990, p. 25). In order to do so, actors have to solve the problem of self-organisation in order to “change the situation from one in which appropriators act independently to one in which they adopt coordinated strategies to obtain higher joint benefits or reduce their joint harm” (Ostrom, 1990, p. 39) and at the same time prevent individuals from harming the CPRs while pursuing their own benefit (what she calls the “free-rider” problem). Ostrom gathered enough worldwide examples that proved not only that having clear and agreed cultural rules of sharing, commoners may easily solve any problem that may arise, but, as David Harvey states, “individuals can and often do devise ingenious and eminently sensible collective ways to manage common property resources for individual and collective benefit” (Harvey, 2012, p. 68). However, she makes clear that “That does not necessarily mean creating an organization. Organizing is a process; an organization is a result of that process” (Ostrom, 1990, p. 39).

Nevertheless, Ostrom is well aware that her theoretical approach is no panacea, as reality is far more complex than what she devised in her game theory:

Such institutional arrangements have many weaknesses in many settings. The herders can overestimate or underestimate the carrying capacity of the meadow. Their own monitoring system may break down. The external enforcer may not be able to enforce ex post, after promising to do so ex ante. A myriad of problems can occur in natural settings, as is also the case with the idealized central-regulation or private-property institutions (Ostrom, 1990, p. 16).

That is precisely what brings her to test if her theoretical proposition can also be an empirical one by thoroughly analysing –on the second part of the book– a series of analysis of study cases of small and medium-sized natural common pool resources such as pastures, water resources, fisheries and the like which have manifest self-organized and stable governance arrangements.

Ostrom was also concerned with finding out if there were patterns that may turn a self-governed CPR into a successful one or, on the contrary, into a failure; and by systematizing a series of anthropological, historical and sociological evidence, she deducted eight so-called “design principles” (Ostrom, 1990, pp. 90-102) for a CPRs to endure:

Clearly defined boundaries, both geographical and social > boundaries for the resource, delimiting who has the right to draw > upon the resources as well as their extension;

Congruence between appropriation and provision rules and local > conditions, or in other words, locally-based rules concerning > the appropriation and provision of the resources;

Collective-choice arrangements: that may allow the participation > of the majority of resource appropriators in the definition of the > arrangements;

Monitoring and auditing performed by or accountable to the > appropriators;

Graduated sanctions that are imposed on those resource > appropriators who violate community rules;

Conflict-resolution mechanisms that are low-cost and local;

Minimal recognition of rights to organise: recognition by > higher-level authorities of the community\’s right to > self-organise;

Nested enterprises: more complex and extensive common-pool > resource (CPR) arrangements should be institutionalised as > multiple layers of nested enterprises, with smaller CPR units as > the base.

As she further explained 16 years later with her former student Charlotte Hess (Hess & Ostrom, 2007, p. 7), these eight design principles are not to be considered as irrefutable models nor any guarantee of success, but “insightful findings in the analysis of small, homogeneous systems”. After all, after conducting a large set of empirical studies on common-pool resource governance, “no single set of specific rules had a clear association with success”. What Ostrom did find out after conducting a large set of empirical studies on common-pool resource governance, is that those eight principles were identified in all successful and robust institutions and yet they were absent in failed systems. However, as they both admitted, “Whether they apply to the study of large and complex systems like knowledge commons is a question for further research” (Hess & Ostrom, 2007, p. 7).

Criticism and reception

This new approach to CPRs is not prone to controversy, as some authors have noted. One of them is the economist and anarcho-libertarian theorist Walter Edward Block, who is very critical9 about Ostrom’s point of view, as he considers not only that commons are in fact a fallacy but that the foundation of free market is the tragedy of the commons.

Block (2011) argues that there are only four possible types of relationship between humankind and nature: 1) Private ownership; 2) Government ownership (socialism); 3) state regulation control of ostensibly private property (what he calls economic fascism) and 4) the commons. According to him, a common is the same as non-ownership, which means that no person or group of people (including the State) should have any rights over it. For those reasons, according to Block, a common “is just as much as an enemy of private ownership as is socialism or fascism” (Block, 2011, p. 2).

He also states that Ostrom makes a mistake when quoting Robert Smith’s words “[it is] by treating a resource as a common property that we become locked in its inexorable destruction” (Ostrom, 1990, p. 12) as she uses it not to support this idea but to criticise it as the benefits of jointly sharing a large grazing area overpasses the benefits and risks of private ownership. According to Block, the fallacy on Ostrom’s discourse is the use of the term jointly since there is no difference with the concept of partnership. Not only that, Block also considers all the examples provided by Ostrom to be in fact mere examples of partnership and not commons at all. Block takes this idea further and states that if the only difference between a common and a large partnership is that whereas in the former case nobody can be excluded from the common resource, and in partnerships there are contracts that rule how a resource and its benefits are to be shared (and ultimately everyone but the partners can be deferred from them), there are no proper commons to talk about. Block argues that in most of the examples of commons provided by Ostrom there is a crucial concept of eligibility underlying by which people opt-in or opt-out to be part of the common, or in other words: whenever there may be specific rules of inclusion and exclusion between commoners/cooperators, it would automatically switch from a common to a partnership. The fact of being something collective is not enough to call something a common since, as Block points out, there are other collective constructions as team sports that can not be considered as such.

Block’s point of view evidences the very contradictory nature of the commons that can be seen on these topics: 1) private and public ownership relationship; 2) exclusion and inclusion criterion; and 3) the fact that there are some cases in which in order to protect a common, this has to be fenced10.

Other authors such as Jonathan Metzger have a more moderate scepticism, which is not related to the commons itself but to Ostrom’s proposal:

To those of us who are not fully persuaded by the gospel, Ostrom’s solution may actually have a little bit of the flavor of Leviathan meets The Prince in the formation of collective but very state-like institutions, and it can be more than a little bit difficult to discern how her suggested solution actually radically diverges from Hardin’s propagation for ‘collectively agreed upon coercion’ beyond the focus on small or medium sized ostensibly self-organized human groups in contrast to Hardin’s supposed (but -nota bene- never stated) focus on more centralized government (Metzger, 2015, p. 31, emphasis in the original).

And later on, he points out that “Many of Ostrom\’s disciples also appear to have extended her argument so as to claim that commons in all situations can be successfully managed in this way.” (Metzger, 2015, p. 31).

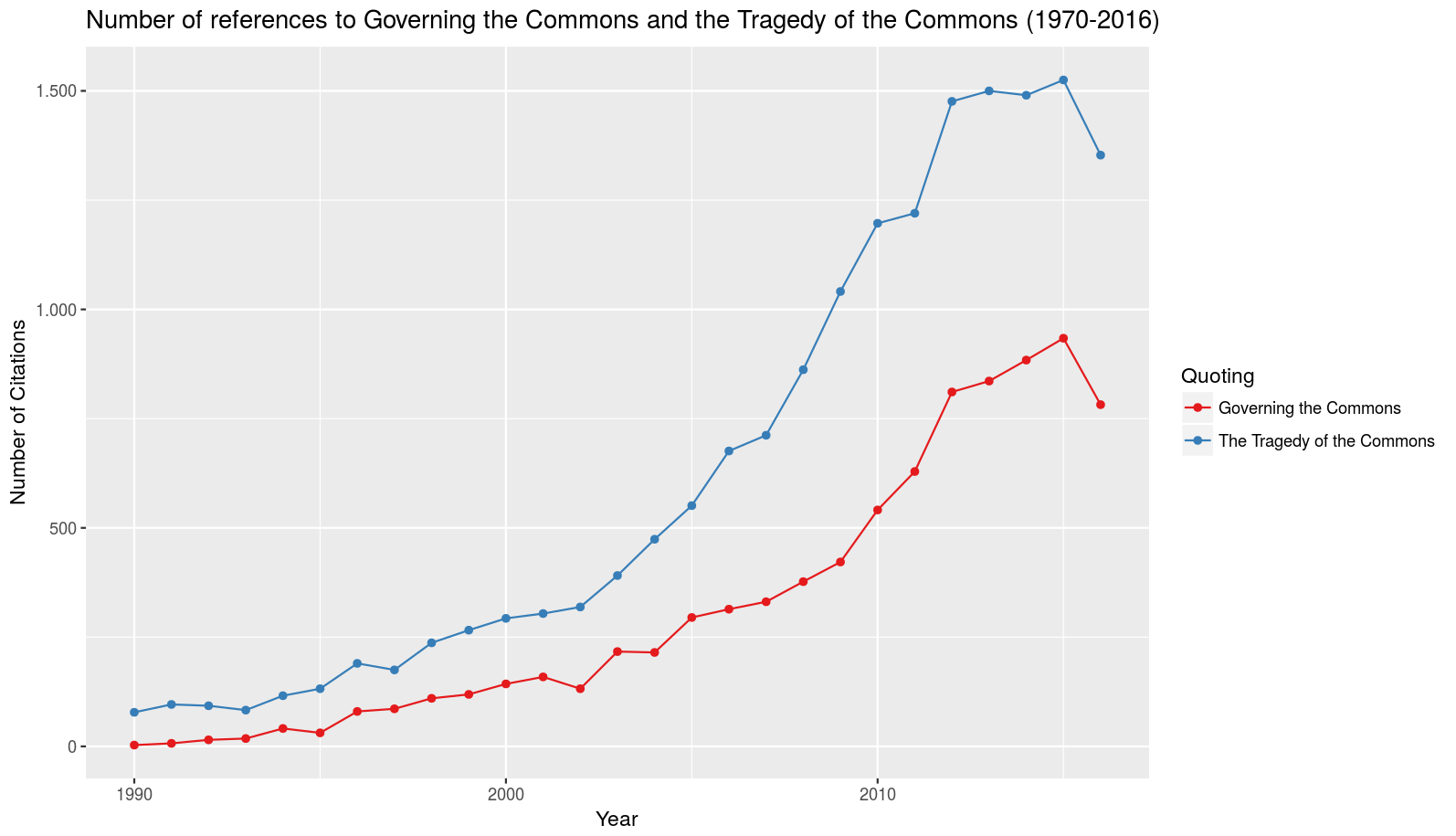

Despite having received some criticism, the broad reception of Ostrom’s work within the scholars’ community cannot be denied, as the figures point out: the number of times that it has been cited since its publication has not only increased till 2009 but has always outnumbered quotes from Hardin’s article (figure 3.1).

Fig. 3.1. Citation numbers for Governing the Commons (Ostrom) and Tragedy of the Commons (Hardin). Source: Scopus (data), CCM..

As Frank van Laerhoven and Erling Berge (2011) argue on the Editorial of International Journal of the Commons’ special issue celebrating the 20th anniversary of Ostrom’s Governing the Commons, its relevance can be attributed to the fact that it made evident how artificial was the dichotomy regarding property rights that was taken for granted. Before her book’s publication there were two only possible options, in which the role of the market, citizens and government change entirely from one to the other. On the one hand there were private goods, which include exclusive goods that can be fenced off from usage to those who do not pay for them. In this group, the market takes provision, production and distribution of goods, whereas citizens are set aside as mere consumers and government has to step in now and then, in order to correct possible market distortions like monopolies, externalities, etc. On the other hand there were public goods, which are non-exclusive and even those who have not contributed or paid for can use them and/or benefit from them. It is Government who is responsible for the delivery and allocation of such goods and citizens, as constituents, have a certain degree of power and decision when dealing with them. Private sector, on the contrary, was not supposed to take part in this equation as no profit can be made out of public goods because it is out of their scope. However, she showed that reality is far more complex and heterogeneous than that: after all, solving problems in public sphere turns out to be non exclusive of governments, citizens can be found to engage in self-organized forms of collective actions with the purpose of providing and producing public goods or CPRs and private-sector business initiate or participate in activities related to creation of public goods or CPRs in innovative ways. Or in other words, problems in the public arena are solved as the result of the interaction between multiple actors: government, civil society actors and private sector entrepreneurs.

But another of Ostrom’s main contributions that can not be overlooked is that it introduced a multidisciplinary approach to the commons research field. Prior to Governing the Commons’ publication, the study of the commons had been limited to the field of biology (it is no wonder that Hardin was a biologist himself), but Ostrom’s approach opened the door to a wider debate which involved many other disciplines which have nothing to do with Earth sciences. This can be confirmed by further analysing the cites received by Governing the commons, grouping them according to their publication’s knowledge areas, which reveal that they come from different fields of studies such as Geography, Economics, Anthropology, Ecology, Forestry, Biology, Public Administration…) (Laerhoven & Berge, 2011, pp. 4-7). This multidisciplinary approach has opened the field for new ways of commons or, how they have often been referred to, “the new commons”.

In fact, Ostrom continued her research on the commons by polishing her research and extending it from natural CPR to other areas previously non-existent, unexplored or unthreatened11, such as outer space, electromagnetic spectrum, information, knowledge or culture. Such new forms of commons that have emerged due to new technologies, as well as others like software, have been thoroughly framed by other scholars and define a completely different approach that is further developed in the next section.

He also provides several more examples that display this tragedy: being companies that pollute a common resource such as the water or families who tend to overfeed their children, which leads to a problem of overpopulation and overfeeding, two of those examples.

[return]In their research on the most influential publications in biology during 20th century, Gary W. Barret and Karen E. Mabry reported Hardin’s Tragedy of The Commons to be the first one (Barrett & Mabry, 2002, p. 284).

[return]As we will further develop, in recent years many scholars have started to question Hardin’s asseveration, being the most notable ones Elinor Ostrom (1990), E.P. Thompson (2009, p. 107) and David Harvey (2012, pp. 28-71), who state that it is private property in cattle and individual utility-maximizing behaviour what really lies at the heart of the problem, rather than the common-property character of the resource and hence, if the cattle was also a common, just like the land, Hardin’s metaphor would not apply.

[return]Van Laerhoven and Ostrom identify the conditions under which Hardin’s tragedy of the commons may come true, which include “participants that: (1) are fully anonymous, (2) have no property rights to the resource system [which means that Hardin was referring to open access instead of commons], (3) cannot communicate, and (4) lack long-term interests in a resource” (Laerhoven & Ostrom, 2007, p. 19). A similar argumentation was also developed by Hess and Ostrom (Hess & Ostrom, 2007, p. 11).

[return]Ostrom starts her book with the following direct and critical statement: “Much that has been written about common-pool resources, however, has uncritically accepted the earlier models and the presumption of a remorseless tragedy” (Ostrom, 1990, p. 7).

[return]Ostrom herself is well aware of that, as she cites several studies based on Hardin\’s work: “The ‘Tragedy of the commons’ has been used to describe such diverse problems as the Sahelian famine of the 1970s (Picardi and Seifert 1977), firewood crises throughout the Third World (Norman 1984; Thomson 1977), the problem of acid rain (R. Wilson 1985), the organization of the Mormon Church (Bullock and Baden 1977), the inability of the U.S. Congress to limit its capacity to overspend (Shepsle and Weingast 1984), urban crime (Neher 1978), public-sector/private-sector relationships in modern economies (Scharpf 1985, 1987, 1988), the problems of international cooperation (Snidal 1985), and communal conflict in Cyprus (Lumsden 1973). Much of the world is dependent on resources that are subject to the possibility of a tragedy of the commons.” (Ostrom, 1990, p. 3).

[return]As Ostrom points out, this position was elaborated by Hardin on a latter article (Hardin, 1978, p. 314), which is in turn based on William Ophuls’ work, who stated that only the need of a Leviathan could fix the tragedy of the commons: “because of the tragedy of the commons, environmental problems cannot be solved through cooperation ... and the rationale for government with major coercive powers is overwhelming.” (Ophuls, 1973, p. 228).

[return]The fact that both positions (“either a \‘private enterprise system\’ or \‘socialism\‘“) are oposites brings Ostrom to lucidly note that if one is to be correct, the other will never be (Ostrom, 1990, p. 13).

[return]Just a glimpse on his article\’s abstract can give us an extent of his disagreement: “The lynchpin perhaps even the very foundation of free market environmentalism is the tragedy of the commons. If we do not have private property rights in land, endangered animal species, fish, trees, etc., then there will be a real danger, as the left wing environmentalists charge, of extinction of these resources.” (Block, 2011).

[return]This is an idea that is partially shared by David Harvey, who further develops it in Rebel Cities (Harvey, 2012, pp. 70-71). However, Harvey notes that this fact may let us erroneously think that the best way to protect a common good is always by denying another, which is what Block states.

[return]Hess and Ostrom argue that new technologies such as the invention of the Internet, have led to new forms or enclosures and, hence, new forms of commons to be preserved: “This trend of enclosures is based on the ability of new technologies to \‘capture\’ resources that were previously unowned unmanaged and, thus, unprotected. This is the case of outer space, with the electromagnetic spectrum, and with knowledge and information.” (Hess y Ostrom, 2007, p. 12).

[return]