The digital approach: commons as peer produced intangibles

At the end of 20th century, a series of profound technological (Software, ICT...) and social changes have led to the transformation of society into what has been framed as the network society (Castells, 2001⁄2003, 2006b, 2010) and where knowledge plays a central role. In addition to this new informationalist paradigm (Castells, 2002, 2006a), the crisis suffered by democratic institutionalization (like government, education, health...) have favoured new social practises which in turn have resulted in new forms of production, distribution and consumption of information, but also in legal changes (being some of them controversial1) and, ultimately, new threads to social justice and, thus, new claims against them. Two of the most notorious movements in this context are Free Software Movement and Free Culture Movement, best exemplified by GNU/Linux for the former and by Creative Commons and collaborative sites like Wikipedia and Open Street Map for the latter. Both movements are in turn rooted into the ethics of the Hacker movement that was born around the Artificial Intelligence Lab from MIT around 1950, which was not ruled by economic interests but by the pleasant, educational and fun benefits of creating and sharing knowledge collectively (Himanen, 2001⁄2002).

The following chapters cover the birth and evolution of these contemporary examples, as theorised by Richard Stallman and Lawrence Lessig and later divulged by Yochai Benkler, and how after having gathered momentum (especially within –but not limited to– non-academic environments), they have provided the ideological, technical and legal foundations that ultimately have profoundly influenced the concept of digital commons.

Software: Free/Libre Open Source Software (FLOSS) and Free Software Movement

Software was born free2: during 1950 and 1960s, software was mostly developed by researchers from universities and academia, where the culture of sharing and peer review had been long established. Consequently, and maybe unconsciously, software adopted that scientific approach and was distributed at no cost and usually accompanied by the source code, should the end user (almost always another researcher) need to make any changes to make it work on their hardware or in case new features were to be added. At that time software distribution was also tied to hardware distribution: software was not seen as something valuable on its own but as a tool to operate a device, just like any other component. As it was seen as a part of a whole (like a screen, a circuit board or a protecting box) only the hardware what was worth to be paid, as it was the whole. Or in other words: the cost of the software was included in the cost of the hardware, for hardware and software were seen as a bundle.

However, as computer science evolved, complexity also increased, and the ecosystem started to change3. As a result, software development turned to be something considerably harder and slower, which, in turn, made the previous business model inefficient: not only hardware manufacturers had to increase the price of their products due to the software complexity, but they started to fail in meeting their final users’ requests (for example, leased machines started to require software support, which was out of the scope of hardware manufacturers as it provided no revenue to them). But the final blow that would split hardware and software for good came from the courts: on January 17th, 1969 the United States vs. IBM antitrust suit was filed with the resolution that bundled software was anti-competitive (Fisher, McKie, & Mancke, 1983; Lopatka, 2000). That resolution consolidated the already growing software industry and although some software was still distributed for free (like UNIX, the most used Operating System at that time –although they slowly changed their policy till their business model shifted completely), most of them were sold under restrictive licences that only allowed final users to make use of their software. Software became a product, and as such, it had to be paid for and had to be protected by copyright laws and by technological means4. Privative (or proprietary) software was born.

This scenario stayed more or less stable until 1985, when Richard Stallman, who was an engineer at MIT5 by that time, published the GNU Manifesto6, a seminal document which would open a new way of conceiving software development and would continue with the birth of GNU Project, GNU Licences and, ultimately, to Free Software movement. The manifesto started explaining what GNU was (a new UNIX-like Operating System that could run UNIX software and which anyone could contribute to and distribute it for free, yet at the same time no one would be able to appropriate it and prevent it from being free); what its current status was (several people had contributed to it and several development tools –such as his famous Emacs– had already been developed or were due to), and making an open call to developers to get involved in the project and contribute to it. The second part of the manifesto is addressed to explain GNU’s benefits to virtually anyone, as he makes distinction between developers/contributors, who may be able to write better code and at the same time redistribute their creations for free, and end-users as a whole, who may be able to use the best possible software without having to be put into an ethical dilemma. But most of the document is addressed to refute possible arguments against it. In his last part, Stallman writes answers to such possible argumentations, most of them addressing the problem of how software developers would be able to make a living with Free Software. Although he claims that most people would still develop without any monetary incentive7, according to him, there is no problem in developers earning money nor even trying to make a living out of it. However, he states that they would earn less money, as most of it came from licences that restrict copying, something he considers that makes no sense at all8, and that for that reason they should look for new diverse and innovative ways to earn money (he provides a number of options, such as porting existing software to GNU or to specific hardware, teaching, hand-holding and maintenance services, donations from satisfied users...).

Later that year, on October 4th 1985, Stallman founded the Free Software Foundation (FSF), a non-profit organisation aimed to secure freedom for computer users by promoting the development and use of free software and documentation9, and as a way to sponsor free software’s flagship: GNU project. However, the first formal definition of free software, which is still valid today, had to wait till next year: as it was published by Richard Stallman on behalf of the Free Software Foundation in February 1986 (Stallman, 1986). According to FSF, software can be considered as free if people who receive a copy of it have the following four freedoms (GNU, 1996):

Freedom 0: The freedom to [run] the program for any purpose.

Freedom 1: The freedom to [study] how the program works, and [change] it to make it do what you wish.

Freedom 2: The freedom to [redistribute] copies so you can help your neighbour.

Freedom 3: The freedom to [improve] the program, and release your improvements (and modified versions in general) to the public, so that the whole community benefits.

Two main conclusions can be outlined out of this definition: The first one is that despite accessing the source code (not just binary files) is not considered a freedom by itself, it is needed in order to satisfy freedoms #1 and #3, otherwise studying and modifying software without it can range from highly impractical to nearly impossible. The second one is that the term “free” has nothing to do with price but with liberty: anyone should be free to do what they please with the software, even selling it10. The fact that the term “free” has two meanings in English has brought a lot of confusion which Stallman has often had to refute with his famous quote “To understand the concept, you should think of ‘free’ as in ‘free speech’ not as in ‘free beer’” (GNU, 1996).

However, this idealistic vision had to survive in a hostile environment ruled by copyright regimes. In fact, that was one of Stallman’s main concerns11: to assure that free software would always be free, no matter what, or in other words, to prevent anyone from appropriating it in their own benefits and as general public’s detriment12. For that reason, in 1989 Richard Stallman published the first version of their GNU General Public License (GPL)13, which was used by all the programs released as part of the GNU project. Its preamble was clear enough in this matter, as it stated that:

The license agreements of most software companies try to keep users at the mercy of those companies. By contrast, our General Public License is intended to guarantee your freedom to share and change free software--to make sure the software is free for all its users. The General Public License applies to the Free Software Foundation\’s software and to any other program whose authors commit to using it. You can use it for your programs, too. (Free Software Foundation, 1989 chap. Preamble).

In order to accomplish those statements, GPL licence offered several mechanisms, being the most outstanding ones the fact that anyone who used a software licensed under GPL should release it along with the licence and the source code (Free Software Foundation, 1989 secs. 1-3); that anyone could use the software for any purpose (Free Software Foundation, 1989 sec. 2); or the fact that the distribution of any modification made to a GPL-licensed software should preserve the same licence and thus shared under the same free terms as the original one (Free Software Foundation, 1989 sec. 6). These actions make a clear distinction between intellectual property and ownership: although the software authors are credited for their authorship, they do not have exclusive control over it, as with proprietary software. As a result, since only some rights are preserved (opposed to the well known “all rights reserved” statement in traditional copyrights), GPL is considered to be the first precursor of Copyleft movement, which will be further developed in next section. Consequently, Free Software addresses an ethical problem as well as a practical one.

However, and no matter how highly-skilled was Stallman in writing code (he had already written many lines of code of broadly used software), he was aware that it would be really challenging, if not impossible, to write a complete operating system on his own, without which Free Software’s spread and usage would only be anecdotal. It is for that reason that, with all the previously mentioned initiatives, Stallman consciously initiated a snowballing movement into which anyone could fit in and contribute to. And actually that is what really happened.

From “Free Software” to “Open Source Software” and “FLOSS”

By 1990, GNU had managed to create everything needed to have a complete operating system but a viable kernel0. However, in the same year, a Finnish student at the University of Helsinki called Linus Torvalds started a personal project in order to develop the most basic part of an Operating System, its kernel (which he would name as Linux). He announced its first prototype publicly in a Minix (a Unix-like system intended for academic use) developers’ newsgroup as a way of surveying the most common needs and invited others to join him. In order to do so, and probably influenced by Stallman’s work14, he also published its source code, first under its own licence, which had a restriction on commercial activity, and two years later adopted GNU GLP License. Despite Torvald’s initial claim that Linux would never be something “big and professional like GNU” (Torvalds, 1991), what started as a personal project contained in a few files of 10,000 lines of code, grew rapidly, turning into a with more than 18 million lines of source code15 developed by thousands of contributors16 which today is used in every domain, from embedded systems to supercomputers, and have secured a place in server installations often using the popular LAMP application stack or mobile devices running Android, while the number of distributions for end users is also growing.

One of the keys of this success can be found in the perfect ecosystem formed by the GNU project, which provided the legal and technological framework needed for such an endeavour. As a result, Linux became the missing piece that was necessary to have a completely free development environment, and for first time in history it was possible to have a computer which only used Free Software. Unfortunately, despite all the tools that were required to achieve that, did in fact exist, it was not easy to find them all and put them together, and in order to make things easier GNU/Linux17 distributions were created, which were complete packages ready to use, even for end users.

Fig. 3.2: A GNU/Linux Distros timeline until 2007. Source: Aleksandar Urosevic (GPL)

Paradoxically, despite these two pieces of the puzzle fit perfectly, the tandem formed by GNU and Linux is, in fact, a marriage of convenience: whereas GNU has a strong political and ethical component (to the point that its vision may be dogmatic), Linux lacks any form of political or ideological discourse, as its motivations were just pragmatical, not political18. In other words, there is no revolution behind Linux other than a technological one, similar to that performed by Henry Ford’s on the production lines19. A new way of producing software based on a bottom-up approach consisting of a distributed network of self-managed volunteers doing plenty of small incremental changes was born.

It is no wonder that such goodness attracted not just volunteer developers, but also companies, some of which decided to adopt it for their own software. However, as more developers and firms that adopted the so-called Bazaar production model (Raymond, 2001), more people started to feel uncomfortable with the “Free Software” term, as it carried some political connotations and produced irrational rejection in corporate environments (mostly because it could easily be associated with not getting money out of it)20. One of these persons with more concerns and a pragmatical view was Eric Raymond (1998), who made an open call to the community to start using the term “open source” instead. With this new term, he wanted to describe the new and more efficient mode of organisation and software production without carrying any political connotation. Later that year Raymond and Bruce Perens founded the Open Source Initiative and provided the first definition derived from the Debian Free Software Guidelines with some notable differences with the one for Free Software21.

This new term was rapidly adopted by influential people like Torvalds or publisher Tim O’Reilly but also had to face stiff opposition like Stallman himself, who considered Free Software as something entirely different and, in fact as a subset of Open Source Software22. As a result, it started a schism between the free software movement and the communities of open source software developers. The main difference between these two groups is the relationship between open source and proprietary software, as Free Software defenders reject any form of proprietary software, whereas Open Source proponents accept it, as they consider it is something good that big companies like Microsoft or Google may make efforts to support open source software to remain competitive.

Several naming have been proposed to address this conflict, and currently the most accepted and widespread one is the term “Free/Libre and Open Source Software” (or FLOSS), which was proposed in 2001 by Rishab Aiyer Ghosh in order to avoid taking sides in the debate between “free software” and “open-source software”, as using it does not necessarily take part in choosing between the two camps.

Paradoxically enough, despite these differences and controversies and despite none of their most prominent authors have ever talked about FLOSS as a Commons, it has highly influenced the way we now understand the Commons and Free culture, to the point that authors like Yochai Benkler consider it as “the quintessential of commons-based per production” (Benkler, 2006, p. 63) as it “[Free Software] has played a critical role in the recognition of peer production, because software is a functional good with measurable qualities” (Benkler, 2006, p. 64).

FLOSS as a social justice movement

Despite the unquestionable growth in computer systems, devices users and developers experienced in the last 20 years has favoured the growth of FLOSS’ supporters, its discourse has gone beyond engineers, hackers, Free Software advocates or savvy users. One of the reasons for this expansion is the one provided by John L. Sullivan23, who argues that FLOSS24 has to be considered as a social movement that has expanded to include broader aims of digital freedom and social justice and started as a rebellion against authoritarian control (a vision which, non-surprisingly, is shared with early hackers) and the belief that a new form of computer freedom advocacy was required. However, Sullivan goes even further claiming that FLOSS movement should be, in fact, considered a social justice movement, as he claims that “Social justice issues have been at the core of the free software movement ever since Stallman crafted the notion of the communitarian ethos that prevents many software projects from being removed from the public domain by introducing public restrictions” (Sullivan, 2011, p. 232). Not only that, according to him, GPL licenses created a new legal alternative to copyright which “provided the rudiments of a rival liberal legal vocabulary of freedom, which hackers would eventually appropriate and transform to include a more specific language of free speech” (Coleman, 2009, p. 424). It is, precisely, this “freedom discourse” which has also highly influenced other social justice movements which despite are not directly related to Free Software “have adopted much of Stallman’s rhetoric as a tool to advance their own social justice aims, thereby broadening the ideological reach of the F/OSS movement to incorporate issues of consumer sovereignty, digital rights and information commons” (Sullivan, 2011, p. 232), and thus, transcended Free Software claims with “larger philosophical issues of free speech and democratic information access” (Sullivan, 2011, p. 237).

Knowledge: Free Culture Movement

One of the social justice movements’ subsets that have adopted the aforementioned “freedom discourse” as one of its key concerns is the Free Culture Movement (FCM), a social movement that pursues the freedom to distribute, reproduce and modify cultural, artistic and creative works as free content25. So, if Stallman has often expressed his concerns against the impossibility to share a software with someone who needs it just because of legal issues26, free culture advocates have extended that demand by arguing not only that it would be improper to refuse to share any type of information for the same reasons, but claiming that the more information is shared, the better, since any cultural production should be considered as a common good and, thus, as a gift to humanity which is to be shared.

As a social movement, FCM has some clear goals, such as promoting participative knowledge and their aim to propose a new production model based on digital commons (Fuster Morell & Subirats, 2015, p. 39) and reform intellectual property regime; and have clearly identified a set of opponents (Diani & Bison, 2004, p. 282), such as political institutions which regulate against their goals and corporations and lobbies that promote monopolistic practices. Additionally, FCM should be considered as a distributed movement of movements that share some sets of values and principles (Fuster Morell & Subirats, 2015, p. 40), which may include Copyleft27, Open Knowledge, Libre Knowledge or Open Data movements.

Most of those FCM core principles and values where announced in Lawrence Lessig’s seminal book from 2004: Free Culture: How Big Media Uses Technology and the Law to Lock Down Culture and Control Creativity, where he claims not only that copyright is an obstacle to cultural production, knowledge sharing and technological innovation, but that are private interests, and not public good, what determine those copyright laws28. Lessig, a lawyer and activist specialised in computer law and intellectual rights29, states that the birth of the Internet has introduced profound and unnoticed changes in the way culture is being produced and shared that are threatening to negatively transform a tradition of cultural production. According to him, the fact that Internet’s architecture makes it really easy, fast and cost less to copy and modify content (Lessig, 2004, pp. 276-277), not only offers excellent possibilities for new ways of cultural production30, but would also make it easier than ever to create derivative works. As a consequence of this ease of creating derivative works, cultural production would experience exponential growth, both qualitative and quantitative. After all, cultural production seldom starts from scratch but is often based on other authors’ works, either improving the original work or simply by mixing elements in an original way31. However, and despite this “traditional” (Lessig, 2004, p. xv) way of cultural production has been accepted and celebrated for years32, recent regulatory changes have completely shifted in the opposite direction, enacting laws that fiercely protect all types of property rights. These regulatory changes favour not author’s but the private interests of an industry based on the distribution and of their copyright and distribution which has seen its business model seriously threatened after the arrival of the Internet and the possibilities of a more efficient regime. This situation, hence, has been treated as an exception and accepted as an unshakable truth, whereas it would have been unacceptable in other contexts33.

According to Lessig, this is an erroneous approach, as not only does not create a debate in order to provide a more comprehensive notion of property and piracy, two fundamental concepts of digital culture34, but biases any possible debate by narrowing the options to only two and excluding ones: “either property or anarchy, either total control or artists won’t be paid” (Lessig, 2004, p. 276). The fallacy of this false dichotomy is that it omits any situation between those extremes, either copyright (all rights reserved) or public domain (no rights reserved). As a result of this biased proceeding, Lessig argues that not only the new creativity possibilities offered by the Internet are going to be unexploited, but a series of freedoms that previously were taken for granted (such as the right to privacy, the right to share and modify software or the right to have an open access for academic publications35) are about to be lost36.

But despite Lessig exposed most of FCM’s key points, and despite his influence on FCM can’t be denied, it is also true that he didn’t provide any formal definition for Free Culture or anything that can resemble the four freedoms that every program should guarantee to be considered as Free Software. On the contrary, “Freedom” is only mentioned in the context that creators should be able to decide how do they want their works to be distributed, so under these terms, Lessig’s notion of freedom, is reduced to a matter of choice, decision or autonomy.

It is no wonder, then, that the notion of “Free Culture” is a controversial one, as its meaning is something dynamic and diffuse that FCM’s proponents adapt and reuse according to their point of view37. For these reasons there have been several attempts at providing a univocal definition, like the collaborative approach at freedomdefined.org aimed to provide clarity on the FCM to better explain their goals and make communications with copyright holders more effective. In order to do so, they started a collaborative document which was originally based on the existing philosophies of free software and open source, on the existing policies of relevant projects like Wikipedia, and on their “strong moral conviction that as many works as reasonably possible should be available to all human beings, as freely as possible” (Freedom defined, 2016). As a result, they reached a “stable” definition38. According to their stable definition, a work or content is to be considered free if it is released under a licence granting the following freedoms without limitation:

The freedom to use and perform the work: The licensee must be > allowed to make any use, private or public, of the work. [...]

The freedom to study the work and apply the information: The > licensee must be allowed to examine the work and to use the > knowledge gained from the work in any way.[...]

The freedom to redistribute copies: Copies may be sold, swapped > or given away for free, as part of a larger work, a collection, or > independently, with no limitations on the amount of information > that can be copied, on who can copy the information or on where > the information can be copied. [...]

The freedom to distribute derivative works: In order to give > everyone the ability to improve upon a work, the license must not > limit the freedom to distribute a modified version (or, for > physical works, a work somehow derived from the original), > regardless of the intent and purpose of such modifications. > However, some restrictions may be applied to protect these > essential freedoms or the attribution of authors […]. (Freedom > defined, 2015)

It is important to note that what makes a work free is the ability for a person to legally and practically exercise their fundamental freedoms in relation to a work. As a result, using a free licence is just a necessary yet not sufficient condition, as it only provides a legal frame. However, a technical framework is required too in order to practically exercise the aforementioned freedoms. So, from a technical perspective, a work has to fulfil the following additional conditions (Freedom defined, 2015):

Availability of source data: Where a final work has been > obtained through the compilation or processing of a source file or > multiple source files, all underlying source data should be > available alongside the work itself under the same conditions. > This can be the score of a musical composition, the models used in > a 3D scene, the data of a scientific publication, the source code > of a computer application, or any other such information.

Use of a free format: For digital files, the format in which the > work is made available should not be protected by patents, unless > a world-wide, unlimited and irrevocable royalty-free grant is > given to make use of the patented technology. While non-free > formats may sometimes be used for practical reasons, a free format > copy must be available for the work to be considered free.

No technical restrictions: The work must be available in a form > where no technical measures are used to limit the freedoms > enumerated above.

No other restrictions or limitations: The work itself must not > be covered by legal restrictions (patents, contracts, etc.) or > limitations (such as privacy rights) which would impede the > freedoms enumerated above. A work may make use of existing legal > exemptions to copyright (in order to cite copyrighted works), > though only the portions of it which are unambiguously free > constitute a free work.

A different, and yet similar, approach to provide a definition is the one initially developed by the non-profit Open Knowledge, with substantial input from other interested parties and initially derived from the Open Source Definition. According to them, an open work must satisfy the following requirements in its distribution (Open Knowledge, 2015):

Open License or Status: The work must be in the public domain or provided under an open license […].

Access: The work must be provided as a whole and at no more than a reasonable one-time reproduction cost, and should be downloadable via the Internet without charge. Any additional information necessary for license compliance (such as names of contributors required for compliance with attribution requirements) must also accompany the work.

Machine Readability: The work must be provided in a form readily processable by a computer and where the individual elements of the work can be easily accessed and modified.

Open Format: The work must be provided in an open format. An open format is one which places no restrictions, monetary or otherwise, upon its use and can be fully processed with at least one free/libre/open-source software tool.

And in order to accomplish condition #1, they define which conditions should a licence fulfil to be considered an Open License, some of them are mandatory whereas others are just optional (Open Knowledge, 2015):

Required Permissions: The license must irrevocably permit (or allow) the following:

Use: The license must allow free use of the licensed work.

Redistribution: The license must allow redistribution of the licensed work, including sale, whether on its own or as part of a collection made from works from different sources.

Modification: The license must allow the creation of derivatives of the licensed work and allow the distribution of such derivatives under the same terms of the original licensed work.

Separation: The license must allow any part of the work to be freely used, distributed, or modified separately from any other part of the work or from any collection of works in which it was initially distributed. All parties who receive any distribution of any part of a work within the terms of the original license should have the same rights as those that are granted in conjunction with the original work.

Compilation: The license must allow the licensed work to be distributed along with other distinct works without placing restrictions on these other works.

Non-discrimination: The license must not discriminate against any person or group.

Propagation: The rights attached to the work must apply to all to whom it is redistributed without the need to agree to any additional legal terms.

Application to Any Purpose: The license must allow use, redistribution, modification, and compilation for any purpose. The license must not restrict anyone from making use of the work in a specific field of endeavour.

No Charge: The license must not impose any fee arrangement, royalty, or other compensation or monetary remuneration as part of its conditions.

Acceptable Conditions: The license must not limit, make uncertain, or otherwise diminish the permissions required in Section 2.1 except by the following allowable conditions:

Attribution: The license may require distributions of the work to include attribution of contributors, rights holders, sponsors, and creators as long as any such prescriptions are not onerous.

Integrity: The license may require that modified versions of a licensed work carry a different name or version number from the original work or otherwise indicate what changes have been made.

Share-alike: The license may require distributions of the work to remain under the same license or a similar license.

Notice: The license may require retention of copyright notices and identification of the license.

Source: The license may require that anyone distributing the work provide recipients with access to the preferred form for making modifications.

Technical Restriction Prohibition: The license may require that distributions of the work remain free of any technical measures that would restrict the exercise of otherwise allowed rights.

Non-aggression: The license may require modifiers to grant the public additional permissions (for example, patent licenses) as required for exercising the rights allowed by the license. The license may also condition permissions on not aggressing against licensees concerning exercising any allowed right (again, for example, patent litigation).

Despite the proposals from Freedomdefined and Open Knowledge for a “Free work” definition have different perspectives on the conditions that a work has to fulfil in order to be considered as free, they share the main key points: the need for establishing specific legal and technical requirements to consider a work to be free, where open licences and open formats play a crucial role. Although there were a number of free licences used by the Free Software Movement, like the aforementioned GPL or Affero, MIT License, BSD… it made little or no sense at all to mention things like compiled or source code, binary files… within a context of cultural creation. And it is precisely for that reason that new types of licences were developed for those specific needs, like the most used one today: Creative Commons.

Creative Commons

Creative Commons is Lawrence Lessig’s proposal on what can be done in order to rebuild the freedom to create, share and access to culture without compromising new forms of expression and communication and, at the same time, is a non-profit organisation supporting Free Culture Movement. Motivated by what he considers an excessive concentration of power39, Lessig (2004, p. xv, 131, 161-168) defends an intermediate position regarding intellectual property rights: a “sensible copyright” (Lessig, 2004, p. 277) that neither reserves all rights to the copyright holder preventing others from making any type of use with the work, neither allowing third parties to do what they please with a work in detriment to their authors’ interests. For this reason, inspired by Stallman’s work, he founded in 2001, along with Hal Abelson (MIT Professor), James Boyle and Eric Salzman (lawyers specialized in cyber-law and intellectual property) and Eric Eldred (online editor), Creative Commons, a non-profit organization devoted to promote “the sharing and use of creativity and knowledge” (Creative Commons; Fuster Morell & Subirats, 2015, p. 31) through free legal and technological tools, which currently is the most visible one behind FCM.

The main representation of these legal tools consists of a set of open licences named “CC licenses” with a broader notion of intellectual property rights which reserve only some rights for their authors, without compromising their own interests (See table 3.1 below). So, instead of having a single licence like GPL that has to fit in for any purpose, Creative Commons provides six different type of licences40 that authors can pick from, according to their needs. This flexibility makes CC licenses appropriate for most types of content that are to be shared publicly (mostly -but not restricted to- publications, music, images or videos, but not software or hardware41).

| Copyright | Creative commons | Public Domain / Fair use | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scope | Set by default | Voluntary: Chosen by creators | Expired copyrights |

| Rights | All Rights reserved | Some rights reserved* | No rights reserved |

| Freedoms | Recognition/None |

|

|

| *: according to creators’ desires |

The way authors can decide which rights they want to reserve is by picking one or several of the following four conditions:

Attribution: the right to be credited for the work.

Non Commercial: the right to prevent or allow third parties to make profit out of the work.

No Derivative Works: the right to prevent or allow third parties to alter the work in any way.

Share alike: the right to entail third parties to release any derivative work under the same original licence.

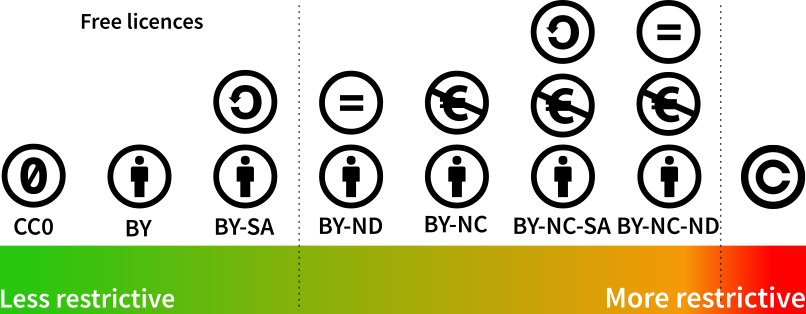

As a result of the combination of those parameters, the following six different type of licences can be obtained, ordered from most to least open:

Public domain: despite in strict sense, it is not a CCLicence, it has often been named as the CC0, as authors can voluntarily opt not to reserve any right about their works. Authors do not have any right over their work, and anyone can do anything with it, without any conditions applicable.

Attribution (CC BY): This licence allows anyone to do anything (distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon) with the work as long as they credit the original author(s).

Attribution – Share-alike (CC BY-SA): This licence allows anyone to do anything (distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon) with the work even for commercial purposes, as long as they credit the original author(s) and licence their new creations under the identical terms.42

Attribution – No derivative (CC BY-ND): This licence allows anyone to redistribute (commercially and non-commercially), as long as it is passed along unchanged and in whole, and they credit their original author(s).

Attribution – NonCommercial (CC BY-NC): This licence allows others to do anything with a work (remix, tweak, and build upon) non-commercially. Although their new works must also acknowledge the original authors and be non-commercial, they don’t have to license their derivative works on the same terms.

Attribution – NonCommercial – Share-alike (CC BY-NC-SA): This licence allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon a work non-commercially, as long as they credit original authors and licence their new creations under the identical terms.

Attribution – NonCommercial – NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND): This licence is the most restrictive of all CC Licences, only allowing others to distribute works as long as they credit their original authors, although it is not possible to change them in any way or use them commercially.

This flexibility introduced by these six CC Licenses, (which is in fact aligned with Lessig’s conception of “freedom”, which seems to be reduced a mere question of choice) by providing a wide spectrum of freedoms regarding creative works is one of the main difference between other Free licences. However, this flexibility introduces a degree of complexity that may make it difficult to chose from. For this reason, Creative Commons developed a tool called ‘CC License chooser’43 and a series of guidelines which aim to help creators to pick the licence that best fits their needs. However, it is important to note that only CC-BY and CC BY-SA licences (in addition to public domain) can be considered as strict “Free licences” in terms of they grant the freedoms that where described at the end of the previous section, whereas the rest of licenses fail on that matter (Figure3.3).

Fig. 3.3: Licences ordered from most to least open. Source: CCM.

Another significant difference between CC Licenses and other types of free licences, is what they call “Three-layer” design, which means that every CC License is, in fact a combination of three different layers: A legal code, an easy to read version of that code, and machine readable code. The first layer of CC Licenses is the legal text which is the only layer that has a legal validity. However, as the language used in this text (like in most legal documents) can be daunting for many creators and people in general who may not be familiar with legal vocabulary, each of these licences are accompanied by a short description called “Legal deed” and a recognizable logo, which conform the second layer. Its goal is to twofold: on the one hand they work as a tag which makes it easy to recognize any document using a CC License, and on the other hand it as provides a brief and easy to understand explanation of what can be done and cannot be done with it and refers to the legal document44. The third layer of a CC License it is aimed at computers. Aware of the importance played by the Internet in terms of distributing and creating derivative works, they provide a “machine readable” version of the license, which is, in fact, a summary of the essential freedoms and obligations written into a standardised format45 that software systems, search engines, and other kinds of technology can understand. By adding this code, it is easy to find any type of content available on the Internet that makes use of a CC License, either using regular search engines or Creative Commons’ specific search engine46.

In summary, Creative Commons redefine and construct new legal meanings to the notions of (free) creative works and intellectual property rights by providing an alternative more sophisticated copyright system based on Stallman’s GPL simple, standardized way to give the public permission to share and use author\’s creative work, but at the same time respecting the conditions chosen by authors themselves. In fact, using the hacker terminology, CC Licenses are a fork of GPL which hack copyright regimes and, thus, challenge the existing intellectual property licences by crafting new freedom discourses.

Common-based peer production

If, as we have just seen, Stallman’s vision has enormously contributed to shaping the FCM by serving as inspiration regarding proceedings and establishing legal frameworks, Torvalds’ has also influenced it in the way of how culture and knowledge can be produced. One of the most prominent scholars that has studied that concept is the Law professor Yochai Benkler47, who named it as “Common-based peer production”.

In 2006, with FLOSS living a high acceptance and expansion and Wikipedia celebrating its 5th anniversary, Benkler published his seminal book The Wealth of Networks (Benkler, 2006) in which he studied the changes suffered in the production and exchange of information, knowledge and culture within the networked society, which according to him are deep and structural48. Most specifically, Benkler elaborates a discourse based on three pillars, technology, social relations49 and market and freedom50, and how do they allow forms of altruistic collaboration between peers (the so-called “common-peer based production”) and their potential transforming consequences for the emergence of the “networked information economy” and its implications for society, politics, and culture.

According to him, and based on a series of economic observations made in the first part of the book, we are facing a new economic paradigm which he calls the “networked information economy” which is characterised by decentralised individual action motivated by reasons other than the economic reward (non-market oriented). This economic paradigm has been made possible due to technological improvements51, especially those related to communication and storage of information and ICT, which are now available to most of the population in developed countries and provide new opportunities for exchanging information, knowledge and culture: the so-called Common-based peer production. This central idea is heavily interlinked with the notion of the commons. However, Benkler’s approach has nothing to do with natural resources, sociology or politics (as the ones that have been developed in section 3.1 and will be developed in 3.3, respectively), but with technology and economy. According to him, the existence of Free/Libre Open Source software or sites like Wikipedia evidence the existence of a new form of production which is “radically decentralized, collaborative, and nonproprietary”52. Another important feature of this new way of producing is that those network of individuals who cooperate with each other to commonly produce something are seldom motivated by future rewards or profit53. In other words: they are not market oriented in terms that they do not rely on market signals or managerial commands or hierarchies.

This particular subset of peer production shares some features with Elinor Ostrom’s framing of the commons, such as the notions of self-managed cooperative networks of individuals and the fact that “no single person has exclusive control over the use and disposition of any particular resource” (Benkler, 2006, p. 61). For Benkler, a commons “refers to a particular institutional form of structuring the rights to access, use, and control resources. It is the opposite of ‘property’ in the following sense: With property, law determines one particular person who has the authority to decide how the resource will be used. That person may sell it, or give it away, more or less as he or she pleases” (Benkler, 2006, p. 60). Or in other words, he understands the commons as open access, and as a result, the aforementioned examples of FLOSS and Wikipedia should be considered as a common. This broad definition of the Commons contrasts with the one provided by Ostrom, as instead of focusing on collective action governance as she did, Benkler considers as a really defining feature of the commons the access conditions to the goods. Far from being contradictory, this generic definition allows Benkler to include digital commons, which due to its non-rival nature could not comfortably fit on Ostrom’s approach.

However, some may find this definition as too narrow. Since it does not consider how collective action takes place, it does not make distinctions between services like Wikipedia and Flickr, software like Android and Firefox, or GNU/Linux distributions like Debian54 and Ubuntu… According to Benkler’s definition, all of them are to be considered as commons despite the fact that some of them are clearly nonmarket oriented (as they are governed by non-profit foundations like Wikimedia, Mozilla or GNU or community of people who share the goals and ideals of the project), whereas others (Flickr, Android or Ubuntu) are driven by big companies like Yahoo!, Google or Canonical respectively and thus ultimately respond to commercial interests55 even though they admittedly have a strong collaborative component in which people participate unselfishly.

As Mayo Fuster (2015, p. 26) lucidly points out, this lack of distinction has prevented Benkler to foresee that, opposed to 2006 context, the open source and digital commons’ panorama has changed dramatically and, 9 years after the writing of The Wealth of Networks, big global corporations like Google, Facebook or Amazon have adopted part of the collaborative discourse into their business models and the majority of the most famous and used forms of digital peer production are now led by companies instead of being community-driven56. Not only that, peer production has extended to new spheres like open hardware and digital fabrication, mapping services, crowd-funding... and ultimately to the business sphere, with new players like Uber or AirB&B57 that perfectly illustrate the controversial so-called “sharing economy”. However, far from invalidating The Wealth of Networks discourse, this new scenario brings a new dimension to it and is still valid as a starting point. In fact, Benkler himself has updated his position in future publications by including these new examples of peer production and making a distinction between “common-based peer production” and “corporate-based peer production” (Benkler, 2013).

After explaining what this new way of (socially) producing is, as well as the economics that is behind that concept58, Benkler claims that common-based peer production explicitly questions the incumbents of the industrial information economy and at the same time creates new opportunities in most areas of people’s lives:

These changes have increased the role of nonmarket and nonproprietary production [...]. These newly emerging practices have seen remarkable success in areas as diverse as software development and investigative reporting, avant-garde video and multiplayer online games. Together, they hint at the emergence of a new information environment, one in which individuals are free to take a more active role than was possible in the industrial information economy of the twentieth century. This new freedom holds great practical promise: as a dimension of individual freedom; as a platform for better democratic participation; as a medium to foster a more critical and self-reflective culture; and, in an increasingly information-dependent global economy, as a mechanism to achieve improvements in human development everywhere. The rise of greater scope for individual and cooperative nonmarket production of information and culture, however, threatens the incumbents of the industrial information economy. (Benkler, 2006, p. 2, emphasis added).

It is in his last part of the book, Policies of Freedom at a Moment of Transformation, where Benkler focuses on the political implications of this new paradigm based on collaboration and freedom and how this can create new forms of collective action that may transform the upcoming political agenda and public policies. According to him, “it is the technological shock, combined with the economic sustainability of the emerging social practices, that creates the new set of social and political opportunities that are the subject of this book” (Benkler, 2006, p. 34), and the field of politics and social action is an example of it.

Fig. 3.4 15M movement in Madrid’s Puerta del Sol. Credits: La información

Again, time has proved Benkler right, as since 2006, there have been many examples of massive collective and self-managed mobilizations and protests for political reasons, such as Arab Spring that started in 2010 in Tunisia and spread to neighbour countries like Egypt, Libya and Yemen and ended forcing off of their respective rulers; “Indignados” Movement that started on May 15th 2011 and concentrated thousands of people in the main public squares of 58 cities in Spain during several weeks in a row protesting against political corruption and austerity measures; or Occupy Wall Street movement.

In Spain, Sociedad General de Autores (SGAE) has pushed hard to approve several laws like the Digital Canon (which was finally abolished on December 31^st^ 2011), known as “Ley Sinde” Ley de Economía Sostenible (2011) or Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (2014) (which ultimately made companies like Google to close their News’ service with a controversial release note -[https://support.google.com/news/answer/6140047?hl=es]). There are also examples of similar experiences worldwide, like the controversial Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA), a United States bill introduced to expand the ability of U.S. law enforcement to combat online copyright infringement and online trafficking in counterfeit goods.

[return]Free not only in terms of open-access but also in the terms that Richard Stallman would define Free Software 30 years later.

[return]Two were the main reasons for such change at the end of 1960’s: the growth of hardware catalogue, now more complex, and the widespread of language compilers that made easier to write code but made binary files impossible to read or modify, only execution was possible.

[return]The most used technique was to distribute only the binary files, which only allow to run the software, tied to a restrictive licence known as EULA or TOS.

[return]Notably enough, MIT was the same place where, at the beginning of 1960, a group of developers called themselves “hackers” and believed that information should be open to anyone and that access to computers should be unlimited as well. For more information about hackers, visit Himanen (2001⁄2002) and Levy (2001).

[return]GNU Manifesto (Stallman, 1985⁄1993) was finally published in 1985 based on Richard Stallman’s announcement text from 1983. Through 1987, it was updated in minor ways to account for developments; since then, it seems best to leave it unchanged, although starting in 1993 several footnotes have been added to clarify several concepts, although the essence has been unchanged. The latest up-to-date version can be found on GNU’s website: [http://www.gnu.org/gnu/manifesto.html]

[return]Stallman stated that “Programming has an irresistible fascination for some people, usually the people who are best at it”, a position is also shared by Pekka Himanen, who further develops the reasons on the hackers’ ethics (Himanen, 2001⁄2002), Eric S. Raymond, who appeals to passion as the main motivation for hackers (Raymond, 2001) and even Linus Torvalds, who suggested that there are only three main motivations to make a person do something: “survival”, “social life” or “entertainment” (Torvalds, 2001).

[return]Stallman argues that “Control over the use of one\’s ideas really constitutes control over other people\’s lives; and it is usually used to make their lives more difficult.” and “People who have studied the issue of intellectual property rights carefully (such as lawyers) say that there is no intrinsic right to intellectual property. The kinds of supposed intellectual property rights that the government recognizes were created by specific acts of legislation for specific purposes.” (Stallman, 1985⁄1993).

[return]Currently, as well as serving as a legal and economical backup for Free Software, it has also promoted campaigns against threats to computer user freedom like Digital Restrictions Management (DRM) and software patents, such as Defective by design or Open Document campaign. For a comprehensive list of campaigns carried out by the Free Software Foundation visit [https://www.fsf.org/campaigns/]

[return]In fact, Stallman was one of the first to earn money from Free Software, as during the first years of GNU Project, he used to sell copies and send them by postal mail.

[return]As it has been pointed out in the previous chapter (3.1 The institutional approach: commons as collectively managed resources), this concern was also shared by Hardin (1968) and would be later be of utmost importance in Elinor Ostrom’s framing of the Commons.

[return]In fact, Stallman himself had suffered from that bad experience, when a private company, Symbolics Inc., hadn’t allowed him to see the improvements they had made to a Lisp interpreter that Stallman had been developing for years and had released it as public domain (Williams, 2002⁄2010 chap. 7).

[return]There have been two subsequent modifications, GPL v.2 (1991) and GPL v.3 (2007), which is the up-to-date version.

[return]In his now famous short message (Torvalds, 1991), he quotes GNU: “I\’m doing a (free) operating system (just a hobby, won\’t be big and professional like gnu) for 386(486) AT clones.“, and in fact he used GNU C Compiler to compile Linux.

[return]- At the time of writing (Version 4.2.3, released in 2015) [return]

Even though just about two percent of the current Linux kernel has actually been written by Torvalds himself (The Linux Information Project, 2006), he is one of the largest contributions to it. These figures give an idea of how complex it is and how many contributors have been involved in Linux.

[return]There has been some controversy on how to call the tandem formed by the kernel (Linux) and operating system (GNU), but the correct term to be used is GNU/Linux (Stallman, 2014). Stallman argues that not using GNU in the name of the operating system unfairly disparages the value of the GNU project and harms the sustainability of the Free Software movement by breaking the link between the software and the free software philosophy of the GNU project.

[return]In fact, Linus Torvalds has publicly rejected any political motivation with statements like “It’s not that you do open-source because it is somehow morally the right thing to do. It’s because it allows you to do a better job. I find people who think open-source is anti-capitalism to be kind of naive and slightly stupid.” (Vance, 2015).

[return]One of the first persons to reflect on this new mode of production was the hacker activist Eric S. Raymond, who, in 1997, named it the Bazaar development model, in opposition to the conventional and centralized development model (which he named “Cathedral model”) followed by most software up to that date (Raymond, 2001). Yockai Benckler would later acknowledge its importance based on voluntary contributions and ubiquitous, recursive sharing, questioned previous assumptions on the way things are produced (Benkler, 2006, pp. 65-66).

[return]As John L. Sullivan points out quoting the work of Dedrick and West when analysing the Free/Open Source Movement as a social movement, “‘the movement ideology’ of access to the source code and more choice for users was found among the true believers of the free software […] but not among organizational adopters, who expressed more pragmatic goals” (Sullivan, 2011, p. 227).

[return]Since it is out of scope of this research to make a thorough explanation of this definition nor to make a comparison with the previous one, we refer to Open Source Initiative (2007).

[return]However, the FSF admits that “the differences in extension of the category are small: nearly all free software is open source, and nearly all open source software is free.” ([https://www.gnu.org/philosophy/categories.html])

[return]In his article, Sullivan (2011) explains FLOSS from the perspective of the four stages that frame any social movement defined by Elliott and Kraemer (Elliott, 2008, pp. 359-380): 1) social unrest; 2) popular excitement; 3) formalization; and 4) institutionalization.

[return]Throughout his essay, Sullivan always uses the terms “F/OSS” or “Free Open Source Software”, although for the sake of clarity and for the reasons aforementioned we will be using the term FLOSS as it is currently more accepted and precise.

[return]According to Sullivan (2011, p. 233), “Stallman’s emphasis on reinvigorating a sense of common good via artistic and other cultural expression has become the philosophical foundation for the larger ‘free culture’ movement”.

[return]“The idea that the proprietary software social system —the system that says you are not allowed to share or change software— is antisocial, that it is unethical, that it is simply wrong, may come as a surprise to some readers. But what else could we say about a system based on dividing the public and keeping users helpless?” (Stallman, 2010, p. 8), although Stallman further develops that idea throughout the whole chapter 2.

[return]“Copyleft” as a play on the word “copyright” and used to refer a copyright licensing scheme in which an author gives in some (but not all) rights under copyright law, was originally conceived by Richard Stallman when he created GPL License. Under copyleft, derived works may be produced provided they are released under the compatible copyleft scheme yet at the same time author still retains some of their rights (hence, the well known statement “Copyleft – some rights reserved”).

[return]Lawrence Lessig credits Stallman as primary source of inspiration to such an extent that he admits that all the ideas that he develops in his book Free culture had already outlined decades before by Stallman and as such, the book could be considered a derivative work of Stallman’s (Lessig, 2004, p. xiv). This statement heavily demonstrates the aforementioned thesis that FSF has highly influenced FCM.

[return]Lessig has long been concerned by the ways in which code (in its two meanings: as understood in computer sciences and law) and more specifically, Internet, can be instruments for social control. He further develops this point of view in his first book: Code (Lessig, 1999).

[return]Some of these new genres like remixes or mash-ups are described in Manovich (2007)‘; Lessig (2008); Shiga (2007). The Internet’s transformative potential is, hence, similar to the revolution introduced by George Eastman in 1888 when he released his cheap Kodak cameras and papers (Lessig, 2004, p. 33).

[return]Lessig provides numerous and notable examples from United States’ recent history to justify his position, one of the most remarkable ones being the case of Walt Disney, whose first animated short that combined synchronized sound and image, Steamboat Willie, was in fact highly influenced by Buster Keaton’s film Steamboat Bill, Jr. released earlier that year (Lessig, 2004, pp. 21-23) and how Disney clearly adapted others’ works in a number of times: Snow White (1937), Fantasia (1940), Pinocchio (1940), Dumbo (1941), Bambi (1942), Song of the South (1946), Cinderella (1950), Alice in Wonderland (1951), Robin Hood (1952), Peter Pan (1953), Lady and the Tramp (1955), Mulan (1998), Sleeping Beauty (1959), 101 Dalmatians (1961), The Sword in the Stone (1963), The Jungle Book (1967), and Treasure Planet (2003) (Ibid., 23–24). This way of cultural production, which he names it as “traditional”, has been accepted and recognized for years: not only Walt Disney’s re-interpretation of fairy tales written by Brothers Grimm have not been prosecuted (Grimm’s works became part of public domain after 30 years of their publication) but have been celebrated and recognized as different, more child-friendly and sweeter, work and a valid creative process.

[return]Again, Lessig lucidly points out the example of Walt Disney’s re-interpretation of fairy tales written by Brothers Grimm, which not only have not been prosecuted (Grimm’s works became part of public domain after 30 years of their publication) but have been celebrated and recognized as different, more child-friendly and sweeter, work and a valid creative process (Lessig, 2004, p. 24).

[return]Lessig provides several examples of similar situations where private interests where notoriously threatened but no regulations supporting them were enacted, such as the loss of Kodak’s emporium of printing copies after digital cameras became mainstream; the loss of rail roads importance in goods’ transportation in favour of motorways or ships; or the weakening of «stickiness of television advertisement» after the invention of remote controls(Lessig, 2004, p. 127).

[return]In fact, Lessig dedicates most of his book to develop those two concepts in Part I (Piracy) and Part II (Property)

[return]Lessig (2004, pp. 277-282) explains how these rights are currently also threatened.

[return]According to him, this may be a no-return point (“A free culture has been our past, but it will only be our future if we change the path we are on right now.” -Lessig 2004, xv), and in the afterword of his book, Lessig reflects on what is to be done in order to change this drift. After considering two groups of actions (“that which anyone can do now, and that which requires the help of lawmakers”), he advocates for a movement that has to start on the streets in order to reach the government (Lessig, 2004, p. 275).

[return]A studio made to 250 Free Culture initiatives in Sao Paulo during 2003 evidenced that there was no direct relationship between the notion of Free Culture used in each initiative and the theoretical approach made by Lessig or Stallman (Reia, 2010).

[return]In addition to this final definition, which has seen two major improvements (current 1.1 version was locked on January 2015), they also have an editable version named “unstable” which is still open to anyone to edit and comment. In fact, at the time of writing this part of the document (February 2016) the latest amend to the definition was made on 4^th^ February 2016.

[return]This vision which is also shared by hackers and FLOSS proponents (Sullivan, 2011, p. 228).

[return]The first set of Creative Commons’ licenses were released one year later after the foundation of the organization, in December 2002. Since then, several modifications have been released, and currently the most up-to-date version, v. 4.0, dates from November 25, 2013. For more information about the latest version, visit: [https://blog.creativecommons.org/2013/11/25/ccs-next-generation-licenses-welcome-version-4-0/]

[return]Although theoretically CC Licenses could be also applied to software and hardware, Creative Commons does not recommend the use of CC licenses for those uses, as “Unlike software-specific licenses, CC licenses do not contain specific terms about the distribution of source code, which is often important to ensuring the free reuse and modifiability of software. Many software licenses also address patent rights, which are important to software but may not be applicable to other copyrightable works. Additionally, our licenses are currently not compatible with the major software licenses, so it would be difficult to integrate CC-licensed work with other free software. Existing software licenses were designed specifically for use with software and offer a similar set of rights to the Creative Commons licenses.” ([https://creativecommons.org/faq/#Can_I_apply_a_Creative_Commons_license_to_software.3F])

[return]This licence is often compared to “copyleft” free and open source software licences, as it does not add any restriction other than all new works based on a work under that licence will carry the same licence, so any derivatives will always be free, which means that will also allow commercial use.

[return]- [https://creativecommons.org/choose/] [return]

To give an idea about the differences between those two texts, we can take the most basic license (CC BY) and compare the legal version ([https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode]) and the legal deed ([https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/]). Whereas the first has an extension of 2.500 words, the latter only has 187 and make use of the aforementioned logos.

[return]This standardised format has been named CC Rights Expression Language (CC REL). For more information on the [https://wiki.creativecommons.org/wiki/CC_REL]

[return]- [http://search.creativecommons.org/] [return]

As Mayo Fuster states in the introduction to the Spanish edition of his book (Fuster Morell, 2015, p. 24), the relevance of The Wealth of Networks relies on the fact that, despite it may not be the first text on these matters, it was the first reference book that comprehensively explained what common-based peer production is, and at the same time, provided resources to interpret and understand its transforming potentialities. Last, but not least, the importance of this book goes beyond the fact that it played a crucial role in drawing attention about that phenomenon to the broader audience, as it also led by example by publishing its contents under Creative Commons’ “Noncommercial Share Alike” licence and by keeping it free to download, not to mention that there have been some editions of this book that have been following a collaborative approach, which is yet another example of common-based peer production. The Spanish edition is an example of this infrequent approach and it is further explained in the Editor’s introduction (Cabello & Alonso, 2015).

[return]“The change brought about by the networked information environment is deep. It is structural. It goes to the very foundations of how liberal markets and liberal democracies have coevolved for almost two centuries.” (Ibid., 1)

[return]Benkler is specially concerned by the changes in social relationships relative to the roles of market and non-market sectors, but instead of providing a sociological approach (like the one provided by Manuel Castells1 centred in the construction of new organizational structures and hierarchies in the form of networks), he considers technical and economic characteristics of computer networks and information as the main drivers of such changes in social behaviours that lead towards a radical decentralization of production.

[return]It is important to note that, despite Benkler acknowledges having a liberal position regarding to freedom (Benkler, 2006, p. 16), what he means by it is not the classical liberal notion of the absence of state coercion, but the modern liberal view of “autonomy”: individuals’ ability to achieve their goals without restraints or manipulations, voluntary or otherwise, by third parties (visit page 9 for more on this). Hence, Benkler’s sympathy for the commons, an institutional framework in which individuals, not a collective, hold property rights. It does not matter for Benkler whether the collective is a private club, such as the participants of an open-source project or the subscribers to a particular information service or the state. What matters is how the commons facilitates “freedom of action” in comparison to how a system of private-property rights affords freedom (P. G. Klein, 2009). This understanding of liberty, which originates with Kant and Rousseau, is central to Benkler’s political economy.

[return]Despite Benkler’s claims against deterministic approaches as being too limited (Benkler, 2006, pp. 16-18) and his statement that it is not networked information technology by itself, but the choices made as society, what may guarantee the improvements in innovation, freedom, and justice that he suggests throughout his book, his discourse may still be considered somewhat techno-deterministic and optimistic (visit Vaidhyanathan (2006) for a detailed point of view on this matter).

[return]By “nonpropietary” Benkler refers to the fact that does not rely on strong copyright agreements as the ones that are broadly used in what he calls industrial information economy (e.g.: traditional business model in publishing or music industries).

[return]Although Benkler admits that some people may in fact be motivated by long-term outcomes in form of money-oriented activities, like consulting or service contracts, the motivation of the majority is more altruistic. This idea was further developed by himself later on (Benkler, 2011) and is also shared by Pekka Himanen (2001⁄2002).

[return]Debian is a GNU/Linux distribution which is known, amongst other things, for its social contract [https://www.debian.org/social_contract] and its code of conduct [https://www.debian.org/code_of_conduct] that any developer has to embrace in order to contribute to the project. Both documents have had several versions (as time of writing the latest versions date from April 26^th^, 2004 and April 28^th^, 2014 respectively) and have been collaboratively written by members of the community.

[return]Benkler may argue that even such examples would still be considered as non-market, for the aforementioned reasons.

[return]For a more comprehensive explanation and examples visit Mayo Fuster’s Ph.D. Theses (Fuster Morell, 2010).

[return]For more information on the motivations that bring people to participate in collaborative consumption networks visit Hamari, Sjöklint, and Ukkonen (2015). The differences between the so-called sharing economy and the commons will be further elaborated in pages 115 and subsequent at the section 4.3 where we develop the limitations of a theoretical approach to urban commons and the risks it entails.

[return]Not in vain, Benkler perspective is that of the market/industry, which can make certain behaviours obsolete when compared to more efficient emerging ones.

[return]